“I’ve always been interested in science and in lizards. I got my first pet lizard when I was around 4 years old, and it was love at first sight,” says Thomas Lozito, Ph.D., who now studies the creatures as an assistant professor of orthopaedic surgery, stem cell biology, and regenerative medicine at the University of Southern California (USC) in Los Angeles.

During his childhood, Dr. Lozito turned his parents’ house into a “little zoo” of lizards and amphibians. He sneaked lizards into his dorm room as a college student at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, Maryland, where he earned his bachelor’s degree in biomedical engineering. While pursuing his Ph.D. in stem cell biology through a joint program between the National Institutes of Health and Cambridge University in England, he bred lizards and frogs and sold them to earn extra money.

Dr. Lozito began studying lizards in the lab as a postdoctoral researcher working with Rocky Tuan, Ph.D., at the University of Pittsburgh in Pennsylvania. He established a lizard colony in Dr. Tuan’s lab, using animals from his personal collection, and studied how they regenerated cartilage—a tough, flexible tissue that gives structure to lizard tails, shark fins, and human noses and ears. Lizards easily regenerate cartilage, but humans struggle to do so, which can lead to health problems. For example, worn-down cartilage in joints—where it’s also found in humans to provide strength and absorb shock—causes osteoarthritis, a painful condition that many people develop as they age. A better understanding of how lizards regenerate cartilage could support the development of treatments that help people do the same.

Establishing a Lizard Lab

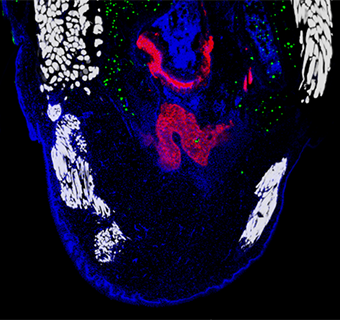

As a faculty member first at the University of Pittsburgh and now at USC, Dr. Lozito has expanded on his postdoctoral work. The goal of his lab is to better understand what factors determine organisms’ regeneration abilities and harness that information to improve healing in people. One of his main research projects is investigating why salamanders, which are amphibians, can regenerate tails that are virtually identical to their original ones, but lizards, which are reptiles, can regenerate only simplified tails. Replacement lizard tails are simple cartilage tubes, while their original ones—and all salamander tails—are dorsoventrally patterned, meaning bone and nerve tissue appear on the upper (dorsal) side and cartilage forms the lower (ventral) side.

One of Dr. Lozito’s biggest achievements so far has been identifying the signaling process that underlies dorsoventral patterning in regrown salamander tails and successfully modifying the process in lizards so that their new tails were patterned. “Lizards have been around for more than 250 million years, and in all of that time, there’s never been one that regenerated a tail with dorsoventral patterning until now,” he says.

Other projects in Dr. Lozito’s lab include:

- Investigating how a species of lizard called the crested gecko lost its ability to regenerate its tail during its evolution. This work could help us understand why mammals, including humans, can’t perform more advanced regeneration despite having many genetic similarities to organisms that can, which could suggest ways to enhance human regenerative abilities.

- Identifying differences between the immune systems of lizards and mice that affect regeneration. Encouraging more lizard-like immune responses in mammals could improve wound healing and reduce scarring.

- Determining which cells trigger regeneration in lizard tails and seeing if they can be used to improve healing in lizard limbs, which don’t regenerate. This work could also lead to novel ways to reduce scarring and encourage new tissue growth.

All the work in Dr. Lozito’s lab supports his 10-year goal: enabling another research organism, a mouse, to regenerate a tail for the first time. While striving toward this long-term goal, he hopes to identify ways to improve the healing of cartilage and the spinal cord. “If we can get regeneration to spark in the mouse by using the lizard as a blueprint, that will get us one step closer to actually affecting human healing and regeneration,” he says.

Introducing Other Scientists to Lizards

In addition to working on his lab’s projects, Dr. Lozito has collaborated with multiple scientists on regeneration-related research. For example, he’s worked with Denis Evseenko, Ph.D., testing a potential medicine that may reduce inflammation and encourage regeneration. They applied the potential medicine to crested geckos after their tails were amputated and found that it reduced scar formation and caused new tail-like appendages to start growing. Dr. Evseenko also found encouraging results in mice, and the potential medicine will soon enter clinical trials that will test its ability to regenerate joint and skin tissues in people.

Dr. Lozito also worked with Michael Bonaguidi, Ph.D., who identified a potential medicine to prevent the loss of neural (nerve) stem cells during aging. They tested it in crested geckos and discovered that it encouraged spinal cord regeneration after tail amputation. The researchers are now investigating whether the potential medicine could be used to treat spinal cord injuries.

Dr. Lozito believes studying lizards could lead to many more unexpected and beneficial discoveries. “Lizards are very underused research organisms, and that’s a shame because they are the closest relatives of humans that have these regenerative capabilities,” he says. “I hope that in the future more scientists give lizards a chance. Every time my lab collaborates with someone and helps them add lizards to their established studies, we find really fascinating things.”

Though Dr. Lozito spends lots of time with lizards at work, it hasn’t at all lessened his interest in keeping them as pets. “I’ve taken full advantage of the warm weather in southern California,” he says. “I built a greenhouse in my backyard where I basically made a little rainforest that I filled with lizard and frog species. I couldn’t be happier.”

Dr. Lozito’s research is supported by NIGMS grant R01GM115444.

This post is a great supplement to Pathways: The Regeneration Issue.

Both this post and Pathways feature Dr. Lozito and his research on regeneration.

Learn more in our Educator’s Corner.

Season Greetings!

I find this article absolutely fascinating, what I want to know is are you testing to see if the tails grows quicker or slower at a particular age both in lizards and salamanders.

I hope your being humane to the these gentle creatures.