Have you ever collected coins, cards, toy trains, stuffed animals? Did you feel the need to complete the set? If so, then you may be a completist. A completist will go to great lengths to acquire a complete set of something.

Scientists can also be completists who are inspired to identify and catalog every object in a particular field to further our understanding of it. For example, a comprehensive parts list of the human body—and of other organisms that are important in biomedical research—could aid in the development of novel treatments for diseases in the same way that a parts list for a car enables auto mechanics to build or repair a vehicle.

More than 15 years ago, scientists figured out how to catalog every gene in the human body. In the years since, rapid advances in technology and computational tools have allowed researchers to begin to categorize numerous aspects of the biological world. There’s actually a special way to name these collections: Add “ome” to the end of the class of objects being compiled. So, the complete set of genes in the body is called the “genome,” and the complete set of proteins is called the “proteome.”

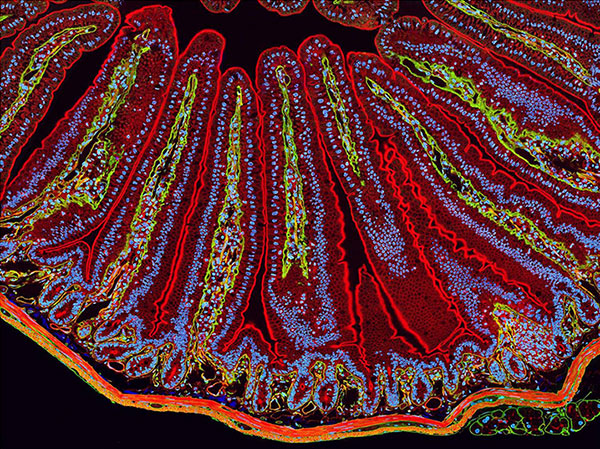

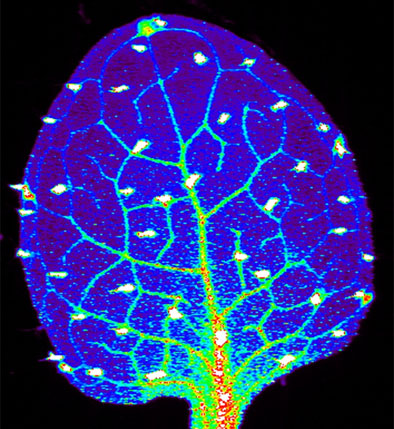

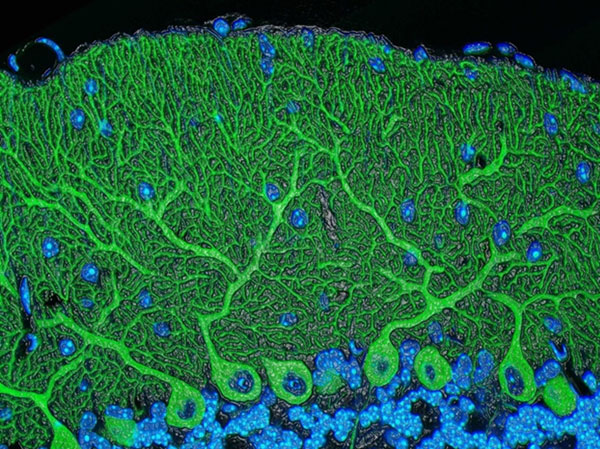

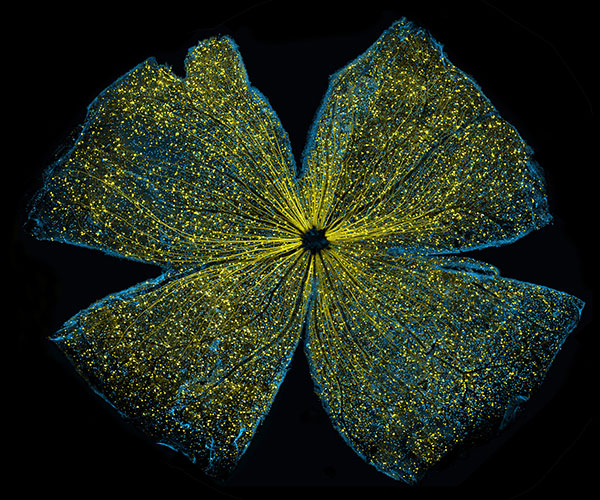

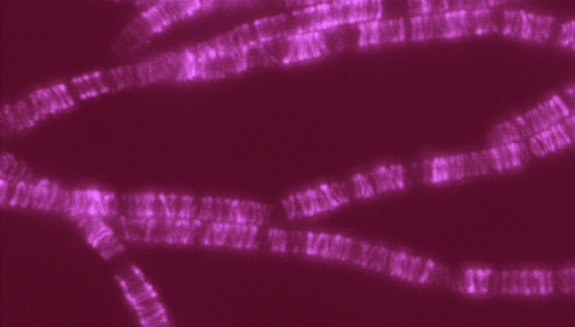

Below are three -omes that NIH-funded scientists work with to understand human health.

Genome

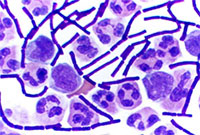

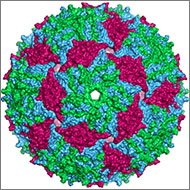

The genome is the original -ome. In 1976, Belgium scientists identified all 3,569 DNA bases—the As, Cs, Gs and Ts that make up DNA’s code—in the genes of bacteriophage MS2, immortalizing this bacteria-infecting virus as possessing the first fully sequenced genome.

Over the next two decades, a small handful of additional genomes from other microorganisms followed. The first animal genome was completed in 1998. Just 5 years later, scientists identified all 3.2 billion DNA bases in the human genome, representing the work of more than 1,000 researchers from six countries over a period of 13 years. Continue reading “There’s an “Ome” for That”