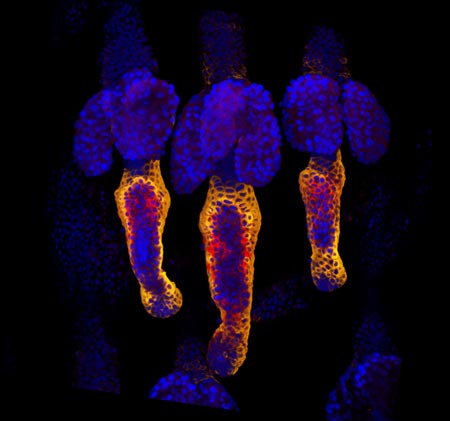

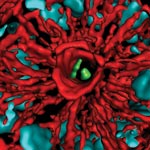

Cancer cells typically include many gene mutations, extra or missing genes, or even the wrong number of chromosomes. Scientists know that certain genetic changes lead to ones elsewhere. But they’ve had a chicken-and-egg problem trying to figure out which changes trigger which others—or whether mutations accumulate randomly in tumors.

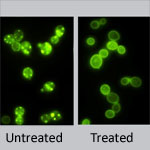

New research led by J. Marie Hardwick ![]() of Johns Hopkins University sheds light on the issue. She found that incapacitating a single gene in yeast cells—regardless of which gene it was—spurred mutations in one or two other genes. The process was anything but random: If, say, gene X was knocked out, yeast cells almost always developed a secondary mutation in gene Y. It’s as if knocking out one gene disrupts the genomic balance enough that the cell must alter a different gene to compensate.

of Johns Hopkins University sheds light on the issue. She found that incapacitating a single gene in yeast cells—regardless of which gene it was—spurred mutations in one or two other genes. The process was anything but random: If, say, gene X was knocked out, yeast cells almost always developed a secondary mutation in gene Y. It’s as if knocking out one gene disrupts the genomic balance enough that the cell must alter a different gene to compensate.

Significantly, the secondary mutations—but not the original ones—caused altered yeast cell characteristics, including traits linked to cancer. Also, many of the secondary mutations occurred in genes associated with cancer in humans, further suggesting that these secondary changes might play a role in carcinogenesis.

This new information will help researchers better understand the chain of genetic events that lead to cancer. It might also prompt scientists to reevaluate years of research that attributed changes in cell behavior or appearance to a given gene knockout.

This work also was funded by NIH’s National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke.

Learn more:

Johns Hopkins University News Release ![]()