When Margaret Sedensky, now of Seattle Children’s Research Institute, started as an anesthesiology resident, she wasn’t entirely clear on how anesthetics worked. “I didn’t know, but I figured someone did,” she says. “I asked the senior resident. I asked the attending. I asked the chair. Nobody knew.”

For many years, doctors called general anesthetics a “modern mystery.” Even though they safely administered anesthetics to millions of Americans, they didn’t know exactly how the drugs produced the different states of general anesthesia. These states include unconsciousness, immobility, analgesia (lack of pain) and amnesia (lack of memory).

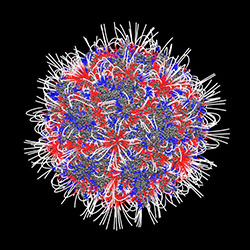

Like the instruments that make up an orchestra, many molecular targets may contribute to an anesthetic producing the desired effect. Credit: Stock image.

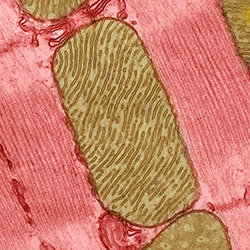

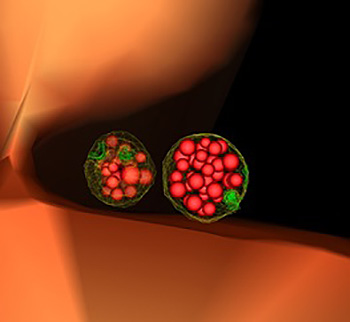

Understanding anesthetics has been challenging for a number of reasons. Unlike many drugs that act on a limited number of proteins in the body, anesthetics interact with seemingly countless proteins and other molecules. Additionally, some anesthesiologists believe that anesthetics may work through a number of different molecular pathways. This means no single molecular target may be required for an anesthetic to work, or no single molecular target can do the job without the help of others.

“It’s like a symphony,” says Roderic Eckenhoff of the University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine, who has studied anesthesia for decades. “Each molecular target is an instrument, and you need all of them to produce Beethoven’s 5th.” Continue reading “Demystifying General Anesthetics”