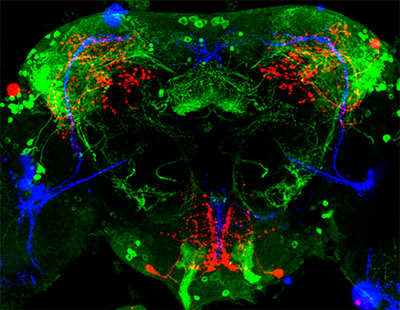

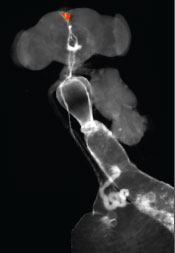

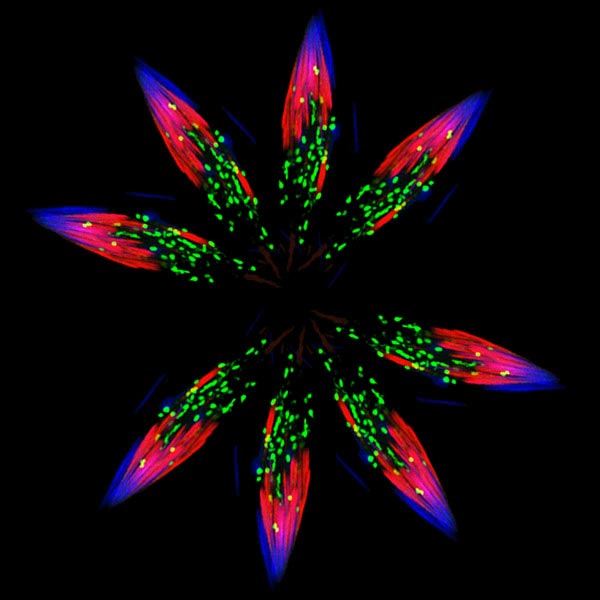

Although it looks like a bursting firework from a Fourth of July celebration, this image actually was created from pictures of spermatids—one stage in the formation of sperm—in the fruit fly (Drosophila). Drosophila is an organism that scientists often use as a model for studying how cells accomplish their amazing tasks. Drosophila studies can help reveal where an essential cellular process goes wrong in diseases such as autoimmune conditions or cancer. Cell death, or apoptosis, is one of these processes.

Almost every animal cell has the ability to destroy itself via apoptosis. Apoptosis is important because it allows the body both to develop normally and get rid of dangerous and unwanted cells when it needs to later in life, such as when cells become cancerous. Many different signals both within and outside the cell influence whether apoptosis happens when it should, and abnormal regulation of this process is associated with some diseases. Hermann Steller ![]() and colleagues at Rockefeller University in New York City study Drosophila and mammalian cells to tease apart the steps of apoptosis and the many molecular signals that regulate it. Continue reading “The Drama of Cell Death”

and colleagues at Rockefeller University in New York City study Drosophila and mammalian cells to tease apart the steps of apoptosis and the many molecular signals that regulate it. Continue reading “The Drama of Cell Death”