Imagine if scientists could zap a single cell (or group of cells) with a pulse of light that makes the cell move, or even turns on or off the cell’s vital functions.

Scientists are working toward this goal using a technology called optogenetics. This tool draws on the power of light-sensitive molecules, called opsins and cryptochromes, which are naturally occurring molecules found in the cell membranes of a wide variety of species, from microscopic bacteria and algae to plants and humans. These light-reacting molecules change their shape or activity when they sense light, so they can be used to trigger cellular activity, such as turning on or off ion flow into the cell and other regulatory pathways. The ability to induce changes in cells has a broad range of practical applications, from enabling scientists to see how cells function to providing the basis for potential therapeutic applications for blindness, cancer, and epilepsy.

Opsins first gained a foothold in research about a decade ago when scientists began using them to study specific electrical networks in the brain. This research relied on channelrhodopsins, opsins that could be used to control the flow of charged ions into and out of the cell. Normally, when a neuron reaches a certain ion concentration, it is triggered to fire, but neuron firing can be changed by inserting opsins in the membrane. Neuroscientists figured out how to incorporate light-sensitive opsin proteins by inserting the opsin gene into the host’s DNA. The genetically encoded opsin proteins in the neuronal membranes could be turned on or off by shining light into the brain itself, using optical fibers or micro-LEDs, to switch on or off the flow of ions and neuron firing.

Since those early studies in the brain, the optogenetics field has come a long way. But the leap from brain cells to other cells has been challenging. Scientists first needed to find a way to deliver light into tissues deep in the body. And, unlike stationary brain cells, they needed a way to target cells that are on the move (such as immune cells). They also needed to develop a way to study not only cell networks but also individual cells and cell parts. The NIGMS-funded researchers highlighted below are among the scientists working to overcome these obstacles and are using optogenetics in new and inventive ways.

Building Bridges

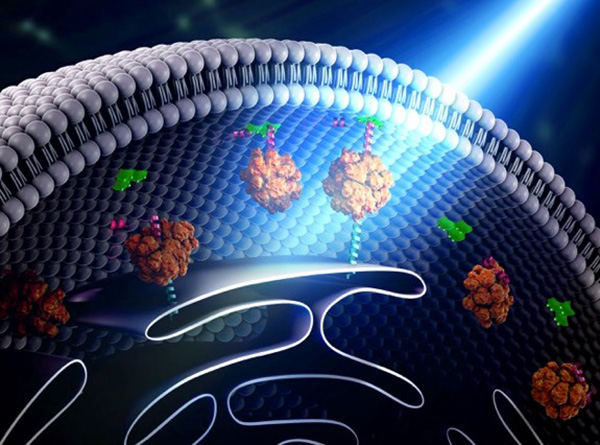

Yubin Zhou of Texas A&M is using optogenetics to control the way cells communicate and to study immune cell function. In one line of research, Zhou is using light to make it easier for calcium ions to enter cells. The ions carry instructions for the cell and also help tether small cellular structures (called organelles). Those inter-membrane tethers allow for the movement of proteins and lipids back and forth across the cell, and are critical for sending chemical messengers to communicate information (see illustration). When this process is disrupted, it can lead to extreme changes in cell function and even cell death. Using this technology to “switch on” normal pathways enables the scientists to better understand how such processes can be disrupted.

Continue reading “Optogenetics Sparks New Research Tools”

Patients can point to one of the faces on this subjective pain scale to show caregivers the level of pain they are experiencing. Credit: Wong-Baker Faces Foundation.

Patients can point to one of the faces on this subjective pain scale to show caregivers the level of pain they are experiencing. Credit: Wong-Baker Faces Foundation.