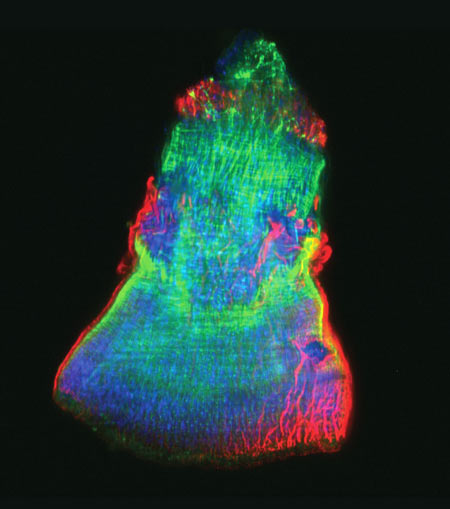

This rainbow-hued image shows the isolated feeding tube, or pharynx, of a tiny freshwater flatworm called a planarian, with the hairlike cilia in red and muscle fibers in green. Scientists use these wondrous worms, which have an almost infinite capacity to regrow all organs, as a simple model system for studying regeneration. A research team led by Alejandro Sánchez Alvarado of the Stowers Institute for Medical Research exploited a method known as selective chemical amputation to remove the pharynx easily and reliably. This allowed the team to conduct a large-scale genetic analysis of how stem cells in a planaria fragment realize what’s missing and then restore it. The researchers initially identified about 350 genes that were activated as a result of amputation. They then suppressed those genes one by one and observed the worms until they pinpointed one gene in particular—a master regulator called FoxA—whose absence completely blocked pharynx regeneration. Scientists believe that researching regeneration in flatworms first is a good way to gain knowledge that could one day be applied to promoting regeneration in mammals.

Learn more:

Stowers Institute News Release

Sánchez Lab