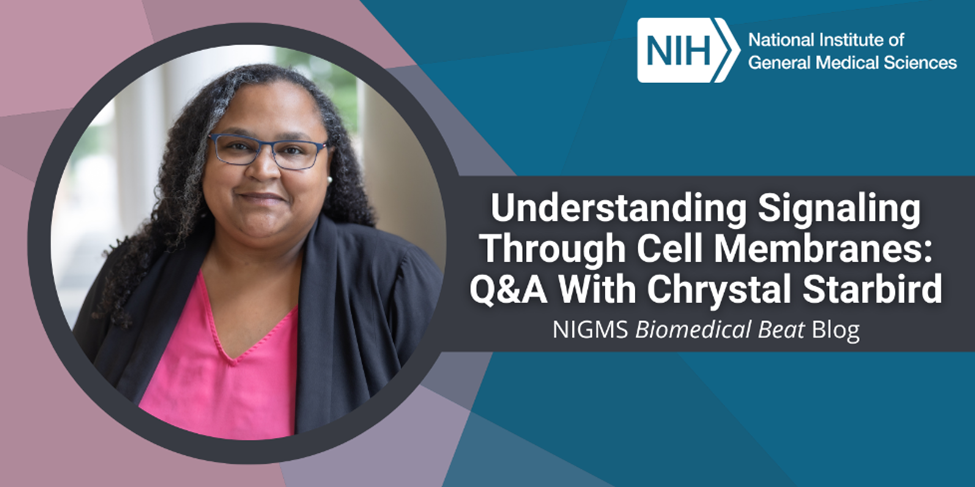

“Science involves constantly learning new techniques, technologies, and equipment so you’re always on the edge of your seat,” says Chrystal Starbird, Ph.D., an assistant professor of biochemistry and biophysics at the University of North Carolina (UNC) in Chapel Hill. We talked with Dr. Starbird about her journey toward becoming a scientist, the support she received from NIGMS training programs, her research on receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs), and her advocacy for science trainees.

Get to Know Dr. Starbird

- Books or movies? Movies

- Favorite music genre? Rap

- Salty or sweet? Salty

- Early bird or night owl? Early bird

- Washing glassware in the lab or dishes in your kitchen? Neither

- Childhood dream job? Basketball player

- Favorite lab tradition? Cleaning day followed by a week off

- Favorite lab technique? Freezing crystals

- Favorite lab tool? Stereoscope

- A scientist (past or present) you’d like to meet? Herman Branson (who discovered the alpha helix, a common structure found in proteins)

Q: How did you become interested in science?

A: At an early age, I was interested in Ranger Rick magazines at school because they had bright, bold pictures of frogs and foxes on the front cover. I wanted everybody to read and enjoy the magazines as much as I did, so when I was in second grade, I started a nature club. Talking with my friends about science as a young person is where it all started for me.

Q: What were your next steps in your science journey?

A: It wasn’t clear to me in middle school or high school that I would be a scientist. In fact, if you’d asked me back then, I would’ve said I was going to be a basketball player and then retire as a lawyer or writer. Although I had many interests and was involved in several activities, my favorite topic in school was always science, so looking back I should have known it was my calling. I applied to undergraduate schools with good science programs to pursue a biology major and planned to attend medical school. As a first-generation college student, I participated in a work-study program that allowed me to work in environmental science and microbiology labs, where I was bitten by the research bug. It seemed powerful to me that you could just ask questions, learn the tools, and find the answers. From that point on, I wanted to pursue research, but my scientific journey was a nonlinear path.

I left school for a while due to family challenges, and after going back and graduating with a biology degree, I worked for a pharmaceutical company in North Carolina, where I learned that having a Ph.D. is valuable in the science community. During that time, I received a phone call from UNC about applying to the Postbaccalaureate Research Education Program (PREP)—an NIGMS-sponsored program that aims to develop a diverse pool of well-trained students who will transition into research-focused doctoral degree programs. To continue working with the pharmaceutical company, I was going to have to eventually relocate, and because moving for a job with my family would have been difficult, 1 year with UNC PREP was a perfect opportunity to start my journey toward becoming a graduate student.

Q: What did you study during graduate school and the rest of your training?

A: As a PREP scholar, I asked questions about the mechanism that controls how bacteria move in response to chemicals. This was when I started to focus on the smaller or simpler parts of larger biological systems as a scientist, guiding me toward becoming a structural biologist. When I advanced from PREP to graduate school at Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tennessee, I focused on mitochondrial proteins involved in energy production, including their role in disease and how they assemble and function. Because my graduate work focused on bacterial systems, I had to take what I learned in bacteria and infer what would happen with similar proteins in humans.

My goal as a postdoctoral (postdoc) researcher was to study human proteins directly involved in disease. To do so, I joined the lab of Kathryn Ferguson, Ph.D., at Yale University in New Haven, Connecticut, who studies RTKs—enzymes located on the cell surface that receive signals from outside of cells. RTKs all have the same general structure—a large domain outside the cell, a kinase domain inside the cell, and a helix connecting the two that’s essentially like a string through the cell membrane. RTKs transfer signals from outside to inside the cell by adding a phosphate group (a phosphorus atom bonded to four oxygen atoms) that then recruits other molecules to carry forward that message. My postdoc project focused on the Tyro3, Axl, and Mer (TAM) family of RTKs because there was very little known about them from a biophysical, biochemical, and structural standpoint, even though there was evidence that TAM receptors were important in various diseases.

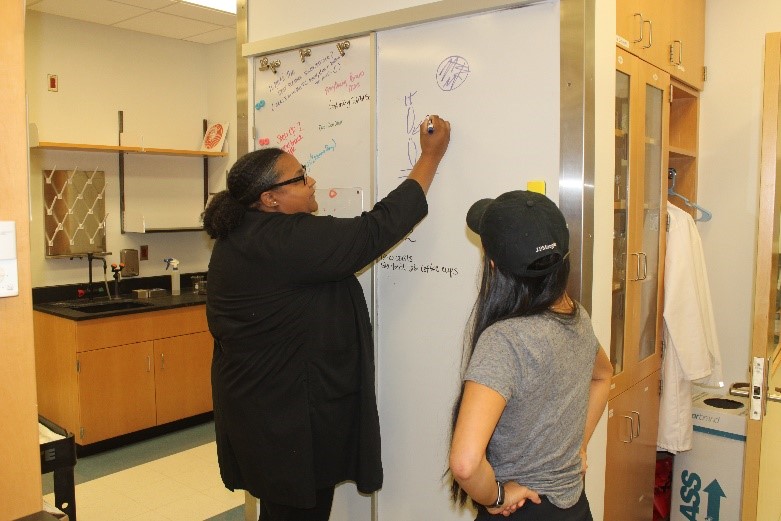

During my postdoc work, I received a grant through the NIGMS Maximizing Opportunities for Scientific and Academic Independent Careers (MOSAIC) program, which has helped facilitate my transition from being a postdoc scholar to having an independent lab. What’s unique about the MOSAIC program is the meaningful and powerful community it builds. When applying for and starting my faculty position at UNC, I reached out to fellow MOSAIC recipients who had gone through the same process for advice, and by sharing their experiences, they were a huge help to me in setting up my lab.

Q: What is your lab’s research focus?

A: In my lab, we’re building on work I started during my postdoc studies focusing on TAM RTKs because we know they’re clinically important but understudied. For a long time, it was hard to understand how a message from outside of the cell could be sent through what is essentially a string in the membrane to the inside of the cell. However, we now know that this messaging occurs through the binding of a molecule to the receptor that causes two RTKs to come together, a process called dimerization. This response leads to the activation of downstream signaling to initiate certain processes, such as cell growth or shrinkage.

My lab uses structural, cellular, and imaging studies to understand how TAM receptors are activated. As structural biologists, we’re at a magical moment where we can look at macromolecular complexes with methods such as cryo-electron microscopy to understand how these complex assemblies form and function at a high level of detail, which could support the development of new treatments for diseases involving RTKs. More specifically, my lab has ongoing studies focused on Alzheimer’s disease and various cancers, and we’re examining the role of TAM receptors in viruses entering cells to initiate infection. I’d also like to study the mechanisms of RTKs in autoimmune diseases such as lupus in the future.

Q: What have been your biggest accomplishments in your career so far?

A: Scientifically, one of my biggest accomplishments is publishing impactful papers on structure-based drug design. For example, I published a paper on bioretrosynthesis, which is a greener and cheaper way to make drugs such as didanosine—an antiviral medication used to treat HIV. Another important accomplishment is my work as an advocate in science. One of the greatest things for me, as a Black woman, has been to talk about my science on big stages. I’ve been involved with the NIH Joint Advisory Committee to the Director and the American Council on Education, providing platforms to share what it’s like to be an underrepresented person pursuing an academic career in science and what can be done better.

Q: What challenges did you have to overcome to reach these accomplishments?

A: Some of the challenges I’ve faced in my pursuit of science have come from being a first-generation student from a low socioeconomic background as well as being a parent while also being a student. For me, the challenges were often financial. In certain cases, when a trainee receives a fellowship, they may lose important benefits from their university like health insurance. This happened to me as a postdoc when I was awarded an F32 fellowship, and I lost health insurance coverage for my family. Another financial challenge is the reimbursement system some universities use, which puts the responsibility of upfront travel costs on the trainees. Even though I had grants to support me attending conferences the entire time I was a student, I only attended one because it took 3 months to be reimbursed by the university, which was devastating to my family.

In addition, most academic systems traditionally haven’t had structures such as childcare in place to support students who are parents. Along with other individuals, I advocated for changes for student parents at my postdoc institution, and today, these obstacles are no longer present there. My successes in advocacy work leading to policy changes have taught me that we can use our voices in impactful ways to make science more accessible for all.

Q: What do you think makes a career in science interesting?

A: This career feels like an amazing privilege to me every single day. Being a scientist is interesting because it involves interacting with people through teamwork or training, and it involves independent work and pushing yourself to understand new things and see what you’re capable of. As a scientist, I also think about how to make society better as a whole or understand a disease that has negatively impacted people.

Q: Do you have any advice for students interested in science?

A: Some of the best scientists are those who go into a lab or an experiment with a plan but feel uncomfortable because they’re unsure if it will work. The important thing is that they’re willing to try. As a faculty member who is training young scientists, I tell trainees that you’re supposed to feel a little bit uncomfortable because you’re learning, growing, and pursuing knowledge that’s unknown. Another piece of advice is to listen to yourself at every stage and routinely check in with yourself to see if what you’re doing is currently interesting, engaging, and fulfilling.

Dr. Starbird’s research receives funding through NIGMS MOSAIC grant R00GM144683. Her graduate work received funding through NIGMS grant F32GM131460. PREP at UNC receives funding through NIGMS grant R25GM089569.