Our internal clocks tell us when to sleep and when to eat. Because they are sensitive to changes in daytime and nighttime cues, they can get thrown off by activities like traveling across time zones or working the late shift. Dysfunction in our internal clocks may lead to insufficient sleep, which has been linked to an increased risk for chronic diseases like high blood pressure, diabetes, depression and cancer.

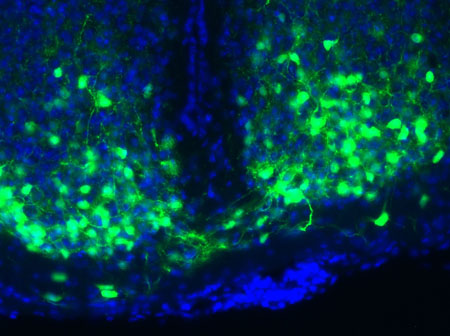

Researchers led by Yi Liu ![]() of the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center have uncovered a previously unknown mechanism by which internal clocks run and are tuned to light cues. Using the model organism Neurospora crassa (a.k.a., bread mold), the scientists identified a type of RNA molecule called long non-coding RNA (lncRNA) that helps wind the internal clock by regulating how genes are expressed. When it’s produced, the lncRNA identified by Liu and his colleagues blocks a gene that makes a specific clock protein.

of the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center have uncovered a previously unknown mechanism by which internal clocks run and are tuned to light cues. Using the model organism Neurospora crassa (a.k.a., bread mold), the scientists identified a type of RNA molecule called long non-coding RNA (lncRNA) that helps wind the internal clock by regulating how genes are expressed. When it’s produced, the lncRNA identified by Liu and his colleagues blocks a gene that makes a specific clock protein.

This inhibition works the other way, too: The production of the clock protein blocks the production of the lncRNA. This rhythmic gene expression helps the body stay tuned to whether it’s day or night.

The researchers suggest that a similar mechanism likely exists in the internal clocks of other organisms, including mammals. They also think that lncRNA-protein pairs may contribute to the regulation of other biologic processes.

Learn more:

University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center News Release

Circadian Rhythms Fact Sheet