Cells rely on garbage and recycling systems to keep their interiors neat and tidy. If it weren’t for these systems, cells could look like microscopic junkyards—and worse, they might not function properly. So constant cleaning is a crucial biological process, and if it goes wrong, accumulated trash can cause serious problems.

Proteasomes: Cellular Garbage Disposals

One of the cell’s trash processors is called the proteasome. It breaks down proteins, the building blocks and mini-machines that make up many cell parts. The barrel-shaped proteasome disassembles damaged or unwanted proteins, breaking them into bits that the cell can reuse to make new proteins. In this way, the proteasome is just as much a recycling plant as it is a garbage disposal.

Three scientists—including two funded by NIGMS—won the 2004 Nobel Prize in chemistry for answering that question. They found that the cell labels its garbage with a tiny protein tag called ubiquitin. Once a protein has the ubiquitin label, the proteasome can grab it, put it inside the barrel, break it down into shorter pieces called peptides, and release the pieces.

Lysosomes: Cellular Stomachs

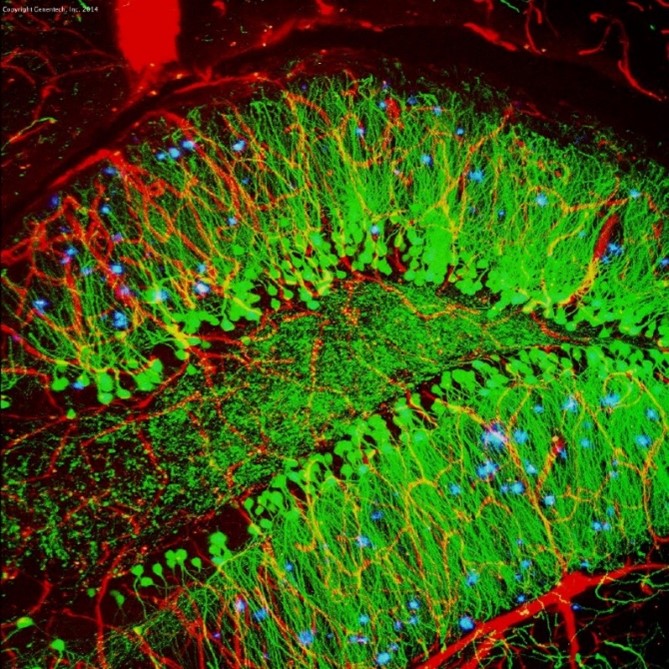

Proteins aren’t the only type of cellular waste. Cells also have to recycle compartments called organelles when they become old and worn out. For this task, they rely on an organelle called the lysosome, which works like a cellular stomach. Containing acid and several types of digestive enzymes, lysosomes digest unwanted organelles in a process termed autophagy, from the Greek words for “self” and “eat.” The multipurpose lysosome also processes proteins, bacteria, and other “food” the cell has engulfed. It even seems to have a role in cell signaling, especially related to nutrient sensing, metabolism, and aging.

If lysosomes can’t digest the garbage, the cell can sometimes spit it out in a process called exocytosis. Once outside the cell, the trash may encounter enzymes that can take it apart, or it may simply form a garbage heap called a plaque. Unfortunately, these plaques can be harmful or lead to disease, like those found between nerve cells in people with Alzheimer’s disease.

Cells also have ways to toss out some poisons that get inside. For instance, cancer cells may pump out medicines that are meant to destroy them, and bacteria may do the same with antibiotics. Scientists are studying how these pumps work, looking for ways to keep the medicines inside where they can do their job.

Further study of the many ways cells take out the trash could lead to new approaches for keeping them healthy and treating or even preventing disease.

Learn more in our Educator’s Corner.