Credit: Janet Iwasa

Janet Iwasa

Fields: Cell biology and molecular animation

Works at: University of Utah

Raised in: Indiana and Maryland

Studied at: University of California, San Francisco, and Harvard Medical School

When not in the lab she’s: Keeping up with her two preschool-aged sons

Something she’s proud of that she’ll never try again: Baking a multi-tiered wedding cake, complete with sugar flowers, for a friend’s wedding.

Janet Iwasa wouldn’t have described herself as an artistic child. She didn’t carry around a sketch pad, pencils or paintbrushes. But she remembers accompanying her father, a scientist at the National Institutes of Health, to his lab on the weekends. She’d spend hours doodling in a drawing program on his old Macintosh computer while he worked on experiments.

“I always remember wanting to be a scientist, and that’s probably highly inspired by my dad,” says Iwasa. Her early affinity for art and technology set her on an unusual career path to become a molecular animator. A typical work day now finds her adapting computer programs originally designed to bring characters like Buzz Lightyear to life to help researchers probe complicated, dynamic interactions within cells.

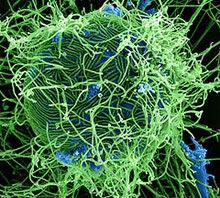

Iwasa’s interest in animation was sparked when she was a graduate student in cell biology, studying a protein called actin, which helps cells to move and change shape. At the time, the only visual representations she had of actin networks were flat, two-dimensional drawings on paper. When she saw an animation of the dynamic movement of a molecule called kinesin, she thought, “Why are we relying on oversimplified, static illustrations [of molecules], when we can be doing something like this video?”

Within a year, she was taking an animation class at a local college. She quickly realized that she would need more intensive instruction to be able to animate complex biological processes. A few summers later, she flew to Hollywood for a 3-month training program in industry-standard animation technology.

The oldest student in that course—and the only woman—Iwasa immediately began thinking about how to adapt a standard animator’s toolkit to illustrate the inner life of cells. A technique used to create the effect of human hair blowing in the wind could also show the movement of an RNA molecule. A chunk of computer code used to make the facets of a soccer ball fall apart and come back together in a different order could be adapted to model virus assembly and disassembly.

Her Findings

Following her training, Iwasa spent 2 years as a National Science Foundation Discovery Corps fellow, producing the Exploring Life’s Origins exhibit with the Boston Museum of Science and the Szostak Lab at Massachusetts General Hospital/Harvard Medical School. As part of the multi-media exhibit, she created animations to illustrate how the simplest living organisms may have evolved on early Earth.

Since then, Iwasa has helped researchers model such complex actions as how cells ingest materials, how proteins are transported across a cell membrane, and how the motor protein dynein helps cells divide.

Iwasa developed this video to show how a protein called clathrin forms a cage-like container that cells use to engulf and ingest materials.

Iwasa calls her animations “visual hypotheses”: The end results may be beautiful, but the process of animation itself is what encapsulates, clarifies and communicates the science.

“It’s really building the animated model that brings insights,” she says. “When you’re creating an animation, you’re really grappling with a lot of issues that don’t necessarily come up by any other means. In some cases, it might raise more questions, and make people go back and do some more experiments when they realize there might be something missing” in their theory of how a molecular process works.

Now she’s working with an NIH-funded research team at the University of Utah to develop a detailed animation of how HIV enters and exits human immune cells.

Abbreviated CHEETAH, the full name of the group is the Center for the Structural Biology of Cellular Host Elements in Egress, Trafficking, and Assembly of HIV.

“In the HIV life cycle, there are a number of events that aren’t really well understood, and people have different ideas of how things happen,” says Iwasa. She plans to animate the stages of viral infection in ways that reflect different proposals for how the process works, to give researchers a new way to visualize, communicate—and potentially harmonize—their hypotheses.

The full set of Iwasa’s HIV-related animations will be available online as they are completed, at https://scienceofhiv.org, with the first set launching in the fall of 2014.

Learn more:

Janet Iwasa’s TED Talk: How animations can help scientists test a hypothesis

Janet Iwasa’s 3D model of an HIV particle was a winner in the 2014 BioArt contest sponsored by Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology

NIH Director’s blog post about Iwasa and her HIV video animation

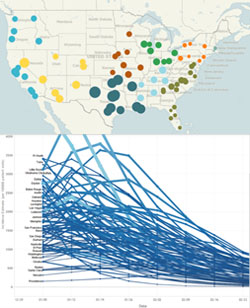

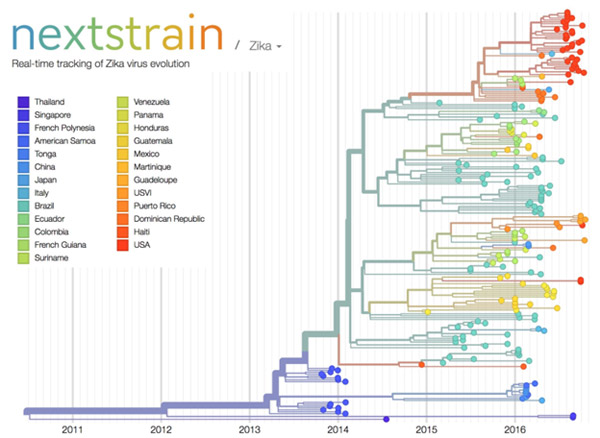

![]() that tracks the spread of emerging viruses such as Ebola and Zika. This tool could be especially valuable in revealing the transmission patterns and geographic spread of new outbreaks before vaccines are available, such as during the 2013-2016 Ebola epidemic and the current Zika epidemic.

that tracks the spread of emerging viruses such as Ebola and Zika. This tool could be especially valuable in revealing the transmission patterns and geographic spread of new outbreaks before vaccines are available, such as during the 2013-2016 Ebola epidemic and the current Zika epidemic.![]() of Biozentrum at the University of Basel, Switzerland—developed nextstrain as an open-access system capable of sharing and analyzing viral genomes. The system mines viral genome sequence data that researchers have made publicly available online. nextstrain then rapidly determines the evolutionary relationships among all the viruses in its database and displays the results of its analyses on an interactive public website.

of Biozentrum at the University of Basel, Switzerland—developed nextstrain as an open-access system capable of sharing and analyzing viral genomes. The system mines viral genome sequence data that researchers have made publicly available online. nextstrain then rapidly determines the evolutionary relationships among all the viruses in its database and displays the results of its analyses on an interactive public website.