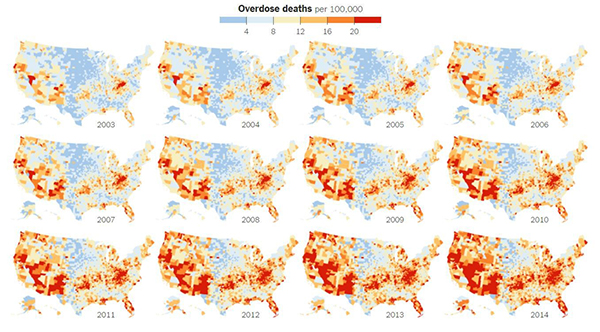

The United States is in the midst of an opioid overdose epidemic. The rates of opioid addiction, babies born addicted to opioids, and overdoses have skyrocketed in the past decade. No population has been hit harder than rural communities. Many of these communities are in states with historically low levels of funding from the National Institutes of Health (NIH). NIGMS’ Institutional Development Award (IDeA) program builds research capacities in these states by supporting basic, clinical, and translational research, as well as faculty development and infrastructure improvements. IDeA-funded programs in many states have begun prioritizing research focused on reducing the burden of opioid addiction. Below is a snapshot of three of these programs, and how they are working to help their communities:

Vermont Center on Behavior and Health

Because there are generally fewer treatment resources in rural areas compared to larger cities, it can take longer for people addicted to opioids in rural settings to get the care they need. The Vermont Center on Behavior and Health works to address this need and its major implications.

“One very disconcerting trend we’re seeing with this recent crisis is that opioid-addicted individuals are being placed on wait lists lasting months to a year without any kind of treatment,” says Vermont Center on Behavior and Health director Stephen Higgins. “And it’s very unlikely that anyone who is opioid addicted is just going to abstain while they are on a wait list.”

In urban areas, buprenorphine—an approved medication for opioid addiction that can prevent or reduce withdrawal symptoms—is generally dispensed by trained physicians at treatment clinics. Unfortunately, many rural communities don’t have enough physicians and clinics to serve patients in need. While waiting for treatment, patients are at risk of premature death, overdose, and contracting diseases such as HIV.

Stacey Sigmon, a faculty member in the Vermont Center on Behavior Health, has developed a method to help tackle this problem: a modified version of a tamper-proof device that delivers daily doses of buprenorphine. The advantage of using the modified device is that it makes each day’s dose available during a preprogrammed 3-hour window within the patient’s home, eliminating the need to visit a clinic.

During a study, participants in the treatment group received interim buprenorphine from the device. They also received daily calls to assess drug use, craving, and withdrawal. Participants in the control group didn’t receive buprenorphine. They remained on the waiting list of their local clinic and didn’t receive phone calls. The results, published in the New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM), indicate that the device works. Participants who received the interim buprenorphine treatment submitted a higher percentage of drug test specimens that were negative for opioids than those in the control group at 4 weeks (88 percent vs. 0 percent), 8 weeks (84 percent vs. 0 percent), and 12 weeks (68 percent vs. 0 percent). Sigmon and colleagues are currently testing the device with a much larger group of participants.

“This tool is now available to other rural states that are also being devastated by this crisis and are not so far along in beefing up treatment capacity,” says Higgins.

In another attempt at alleviating the crunch in treatment capacity, the Vermont Center is preparing to launch a pilot experiment to deliver medication-assisted treatment in the emergency department. Patients presenting opioid misuse issues—e.g., overdose, swelling from using contaminated needles—would get immediate treatment and continue returning to the ER for treatment until a slot opens up at an opioid clinic.

In a different study, Higgins and Sigmon, along with University of Vermont colleagues, addressed another problem associated with opioid misuse—in utero exposure. Nearly 80 percent of all pregnancies in opioid-addicted women are unintended. Higgins and Sigmon found that financial incentives paired with strategies that reduce barriers to introducing contraception—providing contraception without requiring a physical exam and supplying it during the initial visit—greatly increased birth control adherence.

West Virginia Clinical and Translational Science Institute

The West Virginia Clinical and Translational Science Institute (WVCTSI), funded by an IDeA Clinical and Translational Research (CTR) award, strives to bring the best care possible to residents, many of whom live in rural communities. WVCTSI concentrates on five priority health areas, including addiction and resultant emerging epidemics such as hepatitis B, C, and HIV.

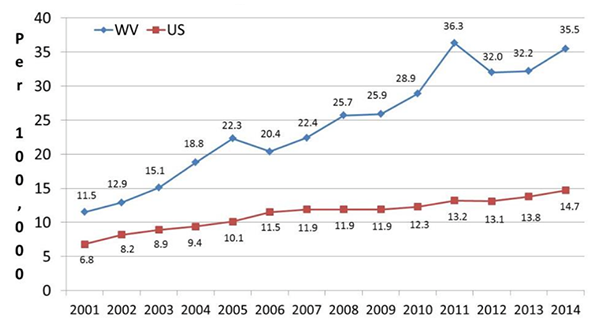

Because opioid overdoses have hit West Virginia particularly hard in recent years, WVCTSI has placed a special emphasis on the study of opioid use disorder (OUD), medically assisted treatment for OUD, and emerging epidemics resulting from OUD.

“The IDeA-CTR is a major stimulus to build research infrastructure that will impact health outcomes in West Virginia, including individuals with OUD,” says WVCTSI director Sally Hodder, M.D.

WVCTSI takes a broad approach to studying opioid addiction, with research in the following areas:

Public health. Approaches include using large databases of electronic medical records to model overdose risk and factors that predict overdose deaths. The CTR has also funded focus groups in five communities across West Virginia. The sessions have hosted up to 20 community stakeholders to discuss underrecognized insights about the opioid crisis and to share deeper strategic concepts that might not otherwise come to the surface. “The idea is that opioid addiction may take a slightly different form in every community,” says Hodder. “And it will be interesting to see what similarities and differences there are among these communities, and what we can learn from them.”

Laboratory science. The CTR has been working with a group of multidisciplinary investigators to shift treatment standards for OUD toward precision medicine. Ongoing studies include investigating opioid misuse in pregnancy as well as genetic variants in mothers and newborns that inform the health of babies born with neonatal opioid withdrawal syndrome (NOWS). In an effort to understand the long-term effects of prenatal opioid exposure on cognition, language, and emotional regulation, CTR researchers at Marshall University School of Medicine perform psychiatric evaluations and cognitive testing of children born with NOWS. (To learn more about NOWS, read this story from the PBS NewsHour that was funded in part by NIGMS’s Science Education Partnership Award (SEPA) program.)

Clinical science. The CTR supports novel strategies to treat OUD. In collaboration with Ali Rezai, a neurosurgeon at West Virginia University, the CTR is gearing up to assess deep brain stimulation (DBS) for treatment-resistant OUD. DBS has previously been used to successfully treat neurological conditions such as Parkinson’s disease, epilepsy, obsessive-compulsive disorder, tremor, and dystonia. In this case, Rezai and his team would implant stimulating electrodes in the brain to modify activity in the nucleus accumbens, a region heavily involved in the brain’s reward circuitry.

Northern New England Clinical and Translational Research Network

Managed by Maine Medical Center Research Institute and the University of Vermont, The Northern New England Clinical and Translational Research (NNE-CTR) Network is a group of academic institutions with portfolios that include research on health issues in rural populations. The network collaborates with the University of Southern Maine, and its partners include Dartmouth Synergy and Tufts University School of Medicine.

Projects funded by the NNE-CTR will place special focus on addiction research. “The center-wide goal is investigating and addressing health care disparities in rural populations,” says NNE-CTR co-director Cliff Rosen.

One way that the NNE-CTR plans to support research into improving the health of opioid-addicted people in rural populations is through various pilot projects, the most successful of which may receive additional funding. “We were a little concerned about whether we would be able to get a significant number of applications for these projects,” says NNE-CTR’s other co-director Gary Stein. “We were hoping, initially, to be able to get 10 or 15 good proposals. We received 35, eight of which focus on the opioid crisis in New England. We were absolutely amazed, and to us this is real validation of an interest in engagement.”

The Vermont Center of Behavior and Health is funded by NIGMS grant P20GM103644. The West Virginia Clinical and Translational Science Institute is funded by NIGMS grant U54GM104942. The Northern New England Clinical and Translational Research Network is funded by NIGMS grant U54GM115516.

To learn more about the opioid crisis in America, visit the PBS NewsHour website to watch segments and read stories on various aspects of the epidemic. The videos and stories were funded in part by NIGMS’ Science Education Partnership Awards (SEPA) program.

Broadcast videos

A community overwhelmed by opioids (10/2/17)

The overwhelming problems faced by Huntington, West Virginia, where the opioid crisis has produced first-responder burnout and overflowing courts, hospitals, and foster care networks. Medical school professor Dr. James Becker told the NewsHour he is seeing rare disease complications and alarming overdose rates.

Understanding the science of pain, with the help of virtual reality (10/4/17)

The mechanics and science of addiction and the multidisciplinary approach—including hypnosis and virtual reality—being taken by those at the University of Washington, the first institution to treat pain as a problem, not just a symptom of something else.

Synthetic opioids are driving an overdose crisis (10/11/17)

The catastrophe of fentanyl, a synthetic opioid that’s roughly 50 to 100 times more potent than morphine and that everyone from clinics to the DEA’s special testing lab in Northern Virginia are trying to get a handle on. Fentanyl was responsible for 80 percent of the overdoses in Massachusetts in 2016.

How an opioid addiction can eat your heart alive (4/30/18)

The heart valve problems of addicts who often face repeat surgeries if they can’t stop taking opioids, as seen from the perspectives of surgeons and a bioethicist.

Website stories

Saving the babies of the opioid epidemic (10/2/17)

The problems faced by addicted newborns who end up in NICU facilities, dosed with methadone and clonidine to get them past their withdrawal. The focus of this segment is the neonatal therapeutic unit at Cabell County-Huntington Hospital in southern West Virginia.

How to safely dispose of pain medication (10/4/17)

A reminder of how NOT to dispose of opioids and alternative safe-disposal methods.

How treating opioids with more opioids has divided the recovery community (10/5/17)

The division among professionals who want to treat addicts with suboxone and other medication assistance and those who insist on a drug-free recovery, as played out in Naples, Florida.

How a brain gets hooked on opioids (10/9/17)

A detailed look on how a brain gets hooked on opioids and how chronic pain patients who deal with mood disorders are at high risk.

Increased prescription of opioid medications led to widespread misuse of both prescription and non-prescription opioids before it became clear that these medications could indeed be highly addictive. Policymakers can create laws about substance abuse prevention and treatment needs in their communities.

The American opioid problem can be attributed to doctor’s. Handing out prescriptions to people in pain, instead of actually treating the people has cause an epidemic. There is no doubt that people get hurt and require assistance but there were no alternatives to these highly addictive prescriptions. The first step is that doctor’s need to know they are a large part of the problem but can be part of the solution. Over prescribing these drugs has led to a crisis that in turn has turned the use of heroin into a problem also. When doctors stop issuing the prescription for the opioids, many people are already addicted. This means they have to find another source for the drugs they need and often this leads to the use of heroin. Doctors have the responsibility to help their patients and not cause more problems. Once doctors decide to issue these prescriptions more sparingly, or better yet, find another solution; the opioid problem will end.

I have been working on a research paper the last couple of weeks for a college course. We as a nation are facing a crisis that is affecting society and ruining lives daily. The National Opioid Crisis started with the pharmaceutical companies introducing OxyContin and labeling it as a drug that had less than a 1% addiction rate. They took advantage of the regulatory changes and aggressively campaigned them.Through the lack of knowledge, training, and mis-labeling of opioids, physicians started over prescribing them. With that came addiction, followed by a national crisis and finally an awareness that we had a problem. The U.S. Senate and House of Representatives passed a series of bipartisan bills aimed at tackling the crisis and pharmaceutical companies were held accountable being fined for mis-branding and labeling opioids as less addictive and less subject to abuse. Although we are aware we have an opioid problem in the U.S. we are still way behind in combating this problem. With the changes we have made to the system, training physicians and medical personnel to recognize addiction, looking for different ways to treat pain and manage it and with the introduction of methadone and buprenorphine we are on the right track. We still have a lot of work to do.