What do antibodies, mucus, and stomach acid have in common? They’re all parts of the immune system!

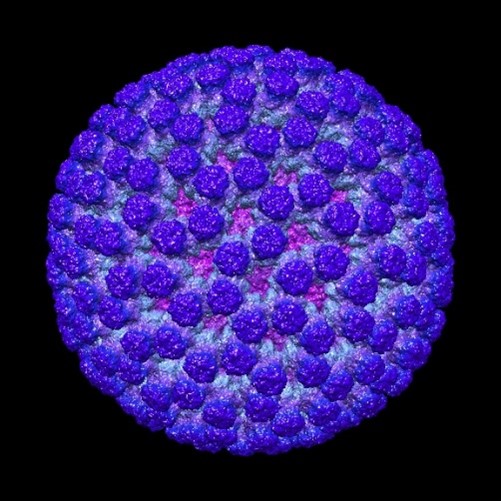

The immune system is a trained army of cells, tissues, and organs that work together to block, detect, and eliminate harmful insults to your body. It can protect you from invaders like bacteria, viruses, fungi, and parasites.

Innate and Adaptive

The immune system is often thought of as two separate platoons: the innate immune system and the adaptive immune system. Although these two platoons have different jobs and are made up of soldiers with different specialties, they work together to prevent infections.

The innate immune system is the first line of defense against infection. Components of the innate immune system include:

- Skin, which provides a physical barrier against invaders

- Mucous membranes in the nose, throat, and lungs, which can trap invaders before they cause infection

- Stomach acid, which can kill microbes in the stomach

- Enzymes, such as lysozyme in saliva and tears, that can kill pathogens by attacking their outer membranes

- Specialized cells called phagocytes, which can detect and clear out microbes

- Tiny proteins floating in the blood called the complement system, which can tag microbes for immune cells to identify and destroy

Cells of the innate immune system work in a nonspecific way, meaning they can detect nearly any microbe by identifying proteins that are only found on microbe surfaces. The innate immune system works immediately (or within a few hours) because it’s always ready to act.

On the other hand, the adaptive immune system is antigen specific, meaning its soldiers have been trained to recognize and attack specific microbes. However, our bodies can’t keep a full stockpile of fighters for every possible type of microbe—there are just too many! For this reason, the adaptive immune system takes several days to mount an effective response as it produces microbe-specific fighters. Soldiers of the adaptive immune system include:

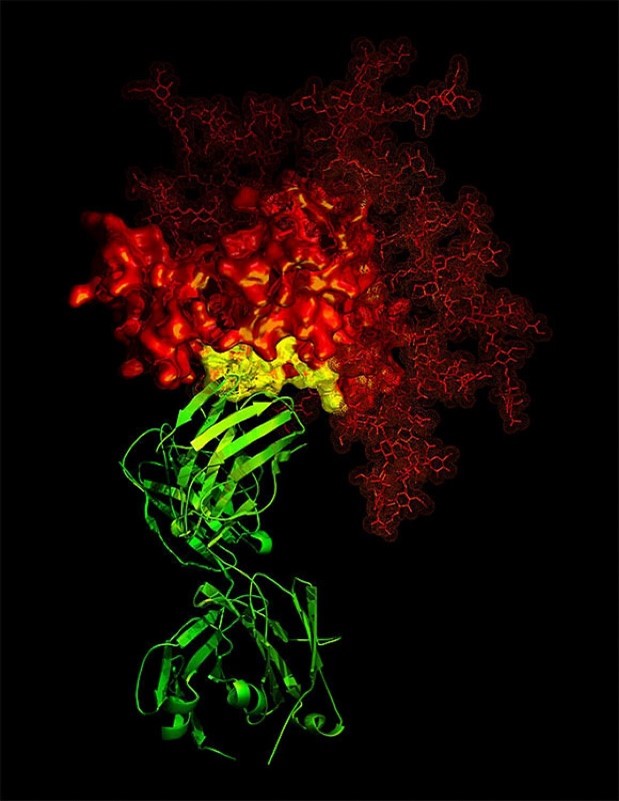

- Antibodies, which are antigen-specific proteins that can bind to the surface of microbes so that cells of the innate and adaptive immune systems can identify and destroy them

- B-cells, which are antigen-specific white blood cells that produce antibodies

- T-cells, which are antigen-specific white blood cells that kill microbes

Immunological Memory

The adaptive immune system gets its name from its ability to remember the pathogens it encounters. Each time your immune system is exposed to a new pathogen, it learns the best way to respond and remembers what it learned. This allows the adaptive immune system to react faster and more effectively the next time it’s exposed to the same invader.

Vaccines generate immunological memory by mimicking infection, but they don’t have the risks infection does. They trick the immune system into mounting a full-scale response to the antigen in the vaccine, which may be a weakened or killed virus, a single protein, or genetic material, such as mRNA. This bit of trickery leads to the development of protective immune memory that can last for many years.

There are many soldiers in the army of the immune system, and we have them all to thank for keeping us healthy!

Find the teaching activity that corresponds with this post in our Educator’s Corner.