In large offices, mailroom workers read the labels on incoming letters and packages to sort and deliver them and dispose of junk mail. In cells, these tasks—as well as importing food and other materials—fall to small cellular sacs called endosomes. Acting as mailroom staff, endosomes sort and deliver nutrients and building blocks, like amino acids, fat and sugars, to their proper destinations, and send cellular junk, like damaged proteins, to trash processors, such as vacuoles or lysosomes.

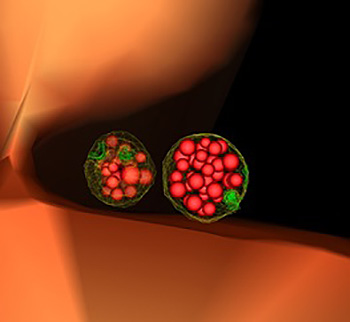

Endosomes form at the cell’s outer surface, the cell membrane. The membrane curves inward as it starts to engulf the desired cargo and then pinches off and seals itself, creating a small bubble inside the cell. As endosomes get older, a similar process starts at their surface—bits of the endosome membrane bend inward and squeeze off even smaller bubbles, called vesicles, that are then housed inside the endosome. Scientists can count these vesicles to estimate the stage of endosomes. Newly formed, or “early,” endosomes don’t have vesicles, whereas more mature, “late” endosomes often have many.

Cells in which normal endosome function is disrupted have problems getting rid of unwanted molecules. Such endosome malfunctions have been linked to neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s. In addition, some viruses, such as HIV and Ebola, use endosomes to hitch a ride into cells. Researchers hope to gain a better understanding of these diseases—and find better ways to treat them—by discovering how endosomes read molecular “mailing labels” to sort and move cellular cargo.

This work was funded by NIH under grants R01GM111335 and T32GM008759.

Very precise! Helped me understand the functions of endosomes well.