Some might think that protein is only important for weightlifters. In truth, all life relies on the activity of protein molecules. A single human cell contains thousands of different proteins with diverse roles, including:

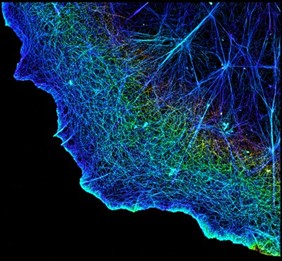

- Providing structure. Proteins such as actin make up the three-dimensional cytoskeleton that gives cells structure and determines their shapes.

- Aiding chemical reactions. Many proteins are biological catalysts called enzymes that speed up the rate of chemical reactions by reducing the amount of energy needed for the reactions to proceed. For example, lactase is an enzyme that breaks down lactose, a sugar found in dairy products. Those with lactose intolerance don’t produce enough lactase to digest dairy.

- Supporting communication. Some proteins act as chemical messengers between cells. For example, cytokines are the protein messengers of the immune system and can increase or decrease the intensity of an immune response.

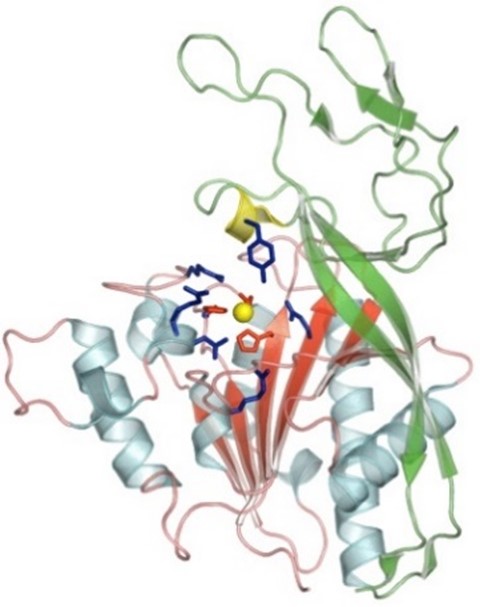

Proteins are chains of amino acids joined by chemical bonds like a string of beads. There are 20 amino acids commonly found in nature, each containing the same backbone structure plus a unique attachment called a side chain. An amino acid’s side chain dictates its behavior. For example, hydrophobic (water-fearing) amino acids will arrange in the center of a protein away from water molecules, while hydrophilic (water-loving) amino acids will arrange on the outside of the protein in contact with water molecules. A protein’s shape and orientation enable it to do its job. Some proteins are only a few dozen amino acids long, while others consist of thousands of amino acids.

Proteins are built based on instructions stored in DNA. First, RNA polymerase copies these instructions in the form of messenger RNA (mRNA), which passes through a cellular “machine” called a ribosome. In a process called translation, the ribosome reads the mRNA and converts it into a chain of amino acids, which then folds into a protein.

Researchers have developed techniques to visualize the 3D shape of a protein, including X-ray crystallography, nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy (NMR), and cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM). Researchers can also gain additional information by changing a protein’s amino acid sequence and seeing how each change affects the protein’s activity. Knowing a protein’s shape, including which section of it controls its function, allows researchers to design therapeutics that turn that function on or off. Most drugs—including treatments for allergies, high blood pressure, and cancer—target proteins.

You can explore 3D structures of proteins (even DNA, RNA, and other biological molecules) in the Protein Data Bank for free! When scientists determine a structure, they upload it to this valuable resource that NIGMS has helped to fund since 1978.

NIGMS-Funded Protein Research

Many NIGMS-supported scientists study proteins. Some of these researchers are:

- Determining the function of enzymes involved in autophagy, a cell’s natural process of recycling old proteins and organelles that goes awry in some diseases like cancer.

- Exploring protein transport within cells and across membranes. Understanding how proteins are properly folded and transported could help generate treatments for diseases such as cystic fibrosis.

- Investigating how antibiotics fight infections by inhibiting ribosomes. Studies like these can lead to new, stronger antibiotics.

- Studying how proteins can misfold and clump together. Improper folding of proteins is common in many neurodegenerative diseases, including Alzheimer’s.

Learn about other scientific terms with the NIGMS glossary.