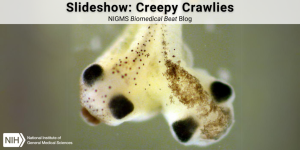

“Water bear” or “moss piglet”? No matter what you call them, tardigrades have secured the title of cutest invertebrate—at least in our book. They’re tiny creatures, averaging about the size of a grain of salt, so while you can spot them with the naked eye, using a microscope is the best way to see them. They earned their nickname of water bear and their official name (which comes from tardigradus, Latin for “slow walker”) because of the way they lumber slowly and deliberately on short, stubby legs.

They’re excellent research organisms due to their translucent bodies and similar anatomy and physiology, including a full digestive system, to that of larger animals. They’ve also been nicknamed moss piglets because they’re often found in moss, but different species of tardigrades have been found in habitats across the earth, from mountaintops to ocean floors and from hot springs to frigid Antarctica.

Tardigrades are known for their ability to survive harsh conditions: extreme cold, boiling heat, intense pressure, lack of oxygen, and even UV radiation in space. But it’s only the species from land, not water, that have evolved this near indestructibility because land environments don’t have the stability that water environments do. These tardigrades can go into a state of extreme hibernation, where their bodies lose almost all their water, shrivel into a ball, and shut down metabolism. Once they’re exposed to water again, they rehydrate and seem to come back to life within a few minutes to hours (although they weren’t technically dead—they just seemed dead).

Thinking about national parks probably brings to mind beautiful views of nature and large animals like bears, moose, and deer. But microorganisms, like tardigrades, are some of the most numerous and diverse organisms in national parks. Many species of tardigrades live in national parks, from the sands of the Fort Matanzas beaches and the rivers of the Great Smoky Mountains to the soil of the Grand Canyon and the potholes of Canyonlands. Tardigrades contribute to their ecosystems by consuming and breaking down the materials around them. Some species are carnivores, some are herbivores, and some are microbivores—meaning their diet consists mainly of microorganisms.

NIGMS-funded scientists study tardigrades to learn new ways to stabilize biologics—materials containing or derived from living organisms like blood, stem cells, antibodies, or vaccines—so they can be stored and transported more easily. Often these products require extreme cold for both storage and transport, which can limit them as an option for people in remote and underdeveloped areas.

So what do you think—water bear or moss piglet? Let us know in the comments below. You can also tell us your favorite research organism, and we might feature it in a future post!

First of all, I think that these are the cutest little microorganisms that I’ve seen my main concern was a word research when describing them what type of research do you do on them? Does it cause pain? Does it cause them to eventually die? Why didn’t we just leave them alone and let them live whatever life they have They are so unbelievably adorable. Of course we could not have them as a pet but they sure are cute. Don’t do any research on them please sincerely, Carolyn.