Hunting for the cause of a disease can be like tracing a river back to its many sources. Myriad factors, large and small, may contribute to a condition. One approach to the search focuses on the massive amounts of genomic and other biological data that scientists are gathering in the course of their studies. To examine this data and look for meaningful patterns and other clues, scientists turn to bioinformatics, a field focused on the development of analytical methods and software tools.

Here are a few examples of how National Institutes of Health-funded scientists are using bioinformatics to dig deeply into data and learn more about the development of diseases, including Huntington’s, preeclampsia and asthma.

Huntington’s Disease

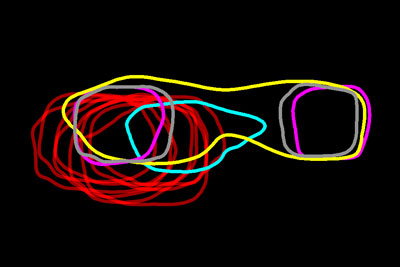

Researchers have mapped a network of 2,141 proteins that all interact either directly or through one other protein with huntingtin (red), the protein associated with Huntington’s disease. Credit: Cendrine Tourette, Buck Institute for Research on Aging,

J Biol Chem 2014 Mar 7;289(10):6709-26

.

The cause of Huntington’s disease, a degenerative neurological disorder with no known cure, may appear simple. It begins with a change in a single gene that alters the shape and functioning of the huntingtin protein. But this protein, whether in its normal or altered form, does not act alone. It interacts with other proteins, which in turn interact with others.

A research team led by Robert Hughes of the Buck Institute for Research on Aging set out to understand how this ripple effect contributes to the breakdown in normal cellular function associated with Huntington’s disease. The scientists used experimental and computational approaches to map a network of 2,141 proteins that interact with the huntingtin protein either directly or through one other protein. They found that many of these proteins were involved in cell movement and intercellular communication. Understanding how the huntingtin protein leads to mistakes in these cellular processes could help scientists pursue new approaches to developing treatments. Continue reading “Digging Deeply Into Data for the Causes of Disease”