Russian nesting dolls. Credit: iStock.

How “membrane-less” organelles help with key cellular functions

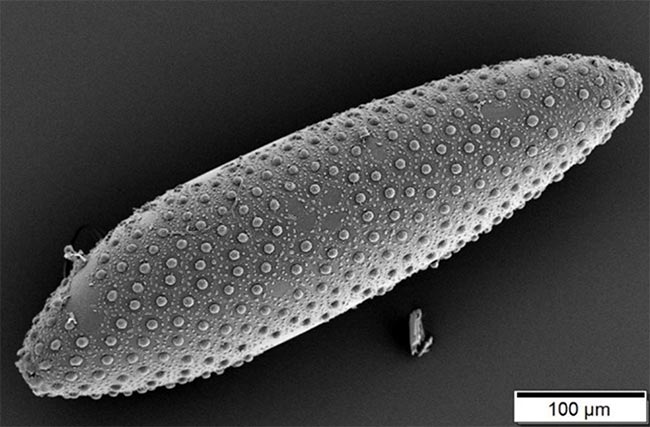

Scientists have long known that animal and plant cells have specialized subdivisions called organelles. These organelles are surrounded by a semi-permeable barrier, called a membrane, that both organizes the organelles and insulates them from the rest of the cell’s mix of proteins, salt, and water. This set-up helps to make cells efficient and productive, aiding in energy production and other specialized functions. But, because of their semi-permeable membranes, organelles can’t regroup and reform in response to stress or other outside changes. Cells need a rapid response team working alongside the membrane-bound organelles to meet these fluctuating needs. Until recently, who those rapid responders were and how they worked has been a mystery.

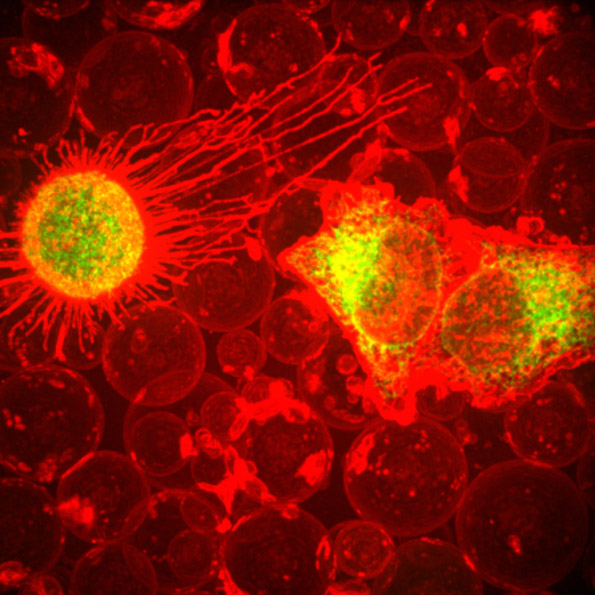

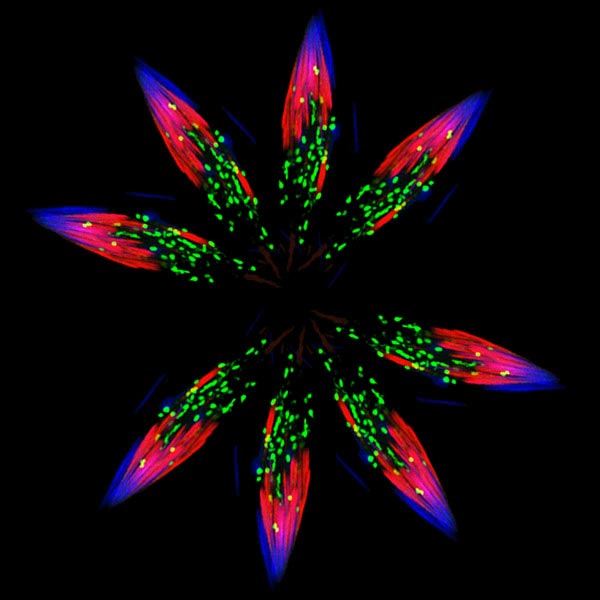

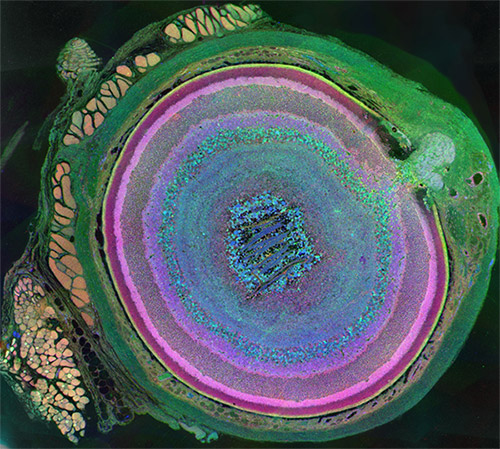

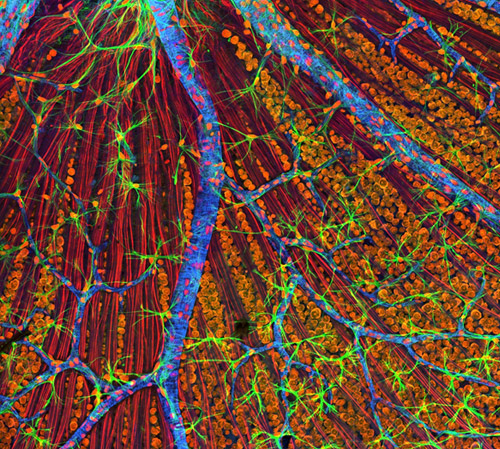

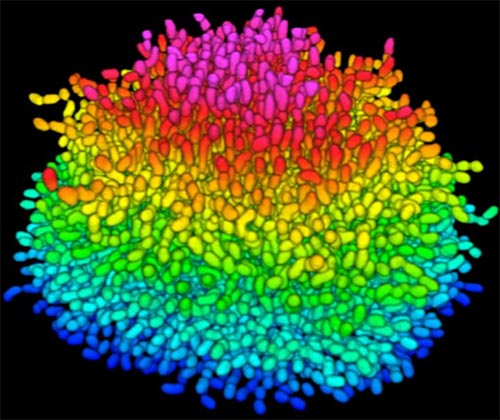

Recent research has led biologists to learn that the inside of a cell or an organelle is not just a lot of different molecules dissolved in water. Instead, we now know that cells contain many pockets of liquid droplets (one type of liquid surrounded by a liquid of different density) with specialized composition and function that are not surrounded by membranes. Because these “membrane-less organelles” are not confined, they can rapidly come together in response to chemical signals, such as those that indicate stress, and equally rapidly fall apart when they are no longer needed, or when the cell is about to divide. This enables membrane-less organelles to be “rapid responders.” They can have complex, multilayered structures that help them to perform many critical cell functions with multiple steps, just like membrane-bound organelles. Scientists even suspect that the way these organelles form as droplets may shed light on how life on Earth first took shape (see sidebar “Could This Be How Life First Took Shape?” at bottom of page).

The Many Membrane-less Organelles

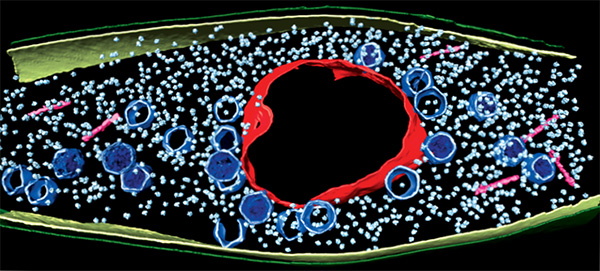

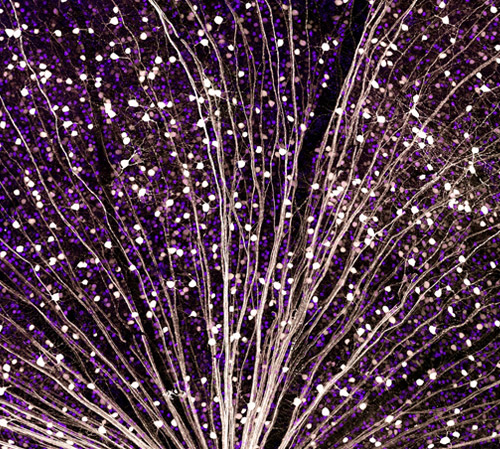

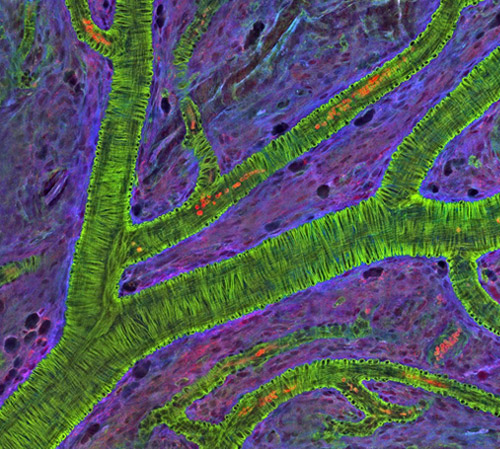

Scientists have identified more than a dozen membrane-less organelles at work in mammalian cells. Several kinds found inside the nucleus—including nuclear speckles, paraspeckles, and Cajal bodies—help with cell growth, stress response, the metabolizing (breaking down) of RNA, and the control of gene expression—the process by which information in a gene is used in the synthesis of a protein. Out in the cytoplasm, P-bodies, germ granules, and stress granules are membrane-less organelles that are involved in metabolizing or protecting messenger RNA (mRNA), controlling which mRNAs are made into proteins, and in maintaining balance, or homeostasis, of the cell’s overall health.

The nucleolus, located inside the nucleus, is probably the largest of the membrane-less organelles. It acts as a factory to assemble ribosomes, the giant molecular machines that “translate” messenger RNAs to make all cellular proteins.

Continue reading “The Changing Needs of a Cell: No Membrane? No Problem!”