During a live online chat dubbed “Cell Day,” scientists at NIGMS recently fielded questions about the cell and careers in research from middle and high school students across the country. Here’s a sampling of the questions and answers, some of which have been edited for clarity or length.

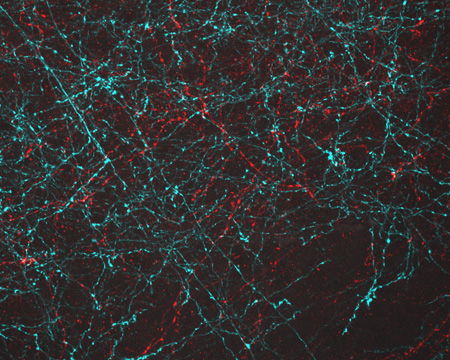

What color are cells?

While cells with lots of iron, like red blood cells, may be red, usually cells are colorless.

How many different types of cells can be found inside the human body?

There are about 200 cell types and a few trillion total cells in the human body. That does not include bacteria, fungi and mites that live on the body.

Is it possible to have too many or not enough cells?

The answer depends on cell type. For example, within the immune system, there are many examples of diseases that are caused by too many or not enough cells. When too many immune cells accumulate, patients get very large spleens and lymph nodes. When too few immune cells develop, patients have difficulty fighting infections.

How fast does it take for a cell to produce two daughter cells?

Some cells, for example bacterial ones, can produce daughter cells very fast when nutrients are available. The doubling time for E. coli bacteria is 20 minutes. Other cells in the human body take hours or days or even years to divide.

Do skin cells stretch or multiply when you gain weight?

The size of cells is tightly regulated and maintained so they do not stretch much. As the surface area of the body increases with weight gain, the number of skin cells increases.

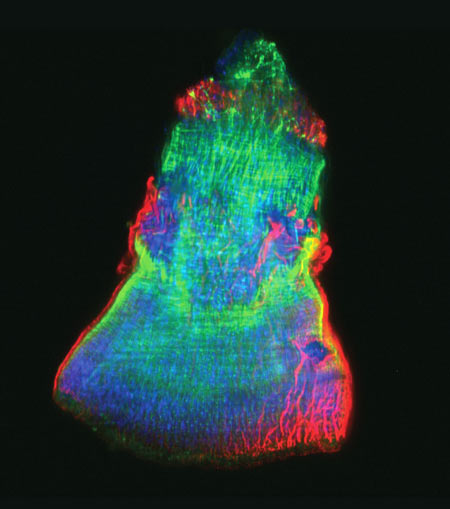

Why do cells self-destruct?

The term for cellular self-destruction is “apoptosis” or “programmed cell death.” Apoptosis is very important for normal development of humans and other animals as it ensures that we do not have too many cells and that “unhealthy” cells can be eliminated without causing harm to the surrounding cells. For instance, did you know that human embryos have webbing between their fingers and toes (just like ducks!)? Apoptosis eliminates the cells that form the web so that you are born with toes and fingers.

In what field is there a need for new scientists?

I would say that there is a need for scientists who can work at the interface between the biological and biomedical sciences and the data sciences. Knowing sophisticated mathematics and having computer skills to address questions like ‘what does this biomedical data tell us about particular diseases’ is still a challenge.

What is a scientist’s daily work day like? Is all of your time spent in a lab testing or like in an office throwing ideas around?

There are lots of different kinds of jobs a scientist can have. Many work in labs where they get to do experiments AND throw ideas around. Working in a lab is a lot of fun—you learn things about the world that no one has known before (how cool is that?). Other important jobs that scientists can do include writing about science as a journalist, helping other scientists patent new technologies they invent as a patent agent or lawyer, or working on important scientific policy issues for the government or other organizations.

Exposure to hypochlorous acid causes bacterial proteins to unfold and stick to one another, leading to cell death. Credit: Video segment courtesy of the American Chemistry Council. View video

Exposure to hypochlorous acid causes bacterial proteins to unfold and stick to one another, leading to cell death. Credit: Video segment courtesy of the American Chemistry Council. View video