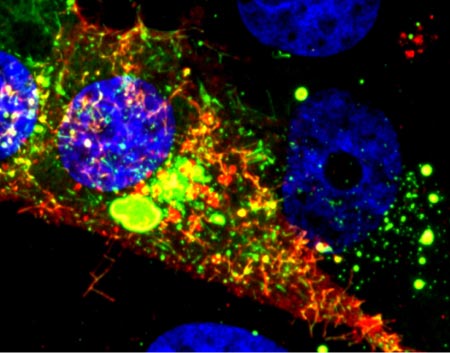

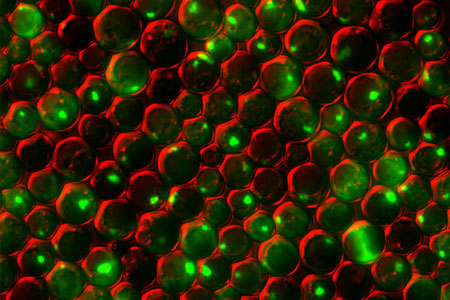

Living things are chatty creatures. Even when they’re not making actual sounds, organisms constantly communicate using chemical signals that course through their systems. In multicellular organisms like people, brain cells might call, “I’m in trouble!” signaling others to help mount a protective response. Single-celled organisms like bacteria may broadcast, “We have to stick together to survive!” so they can coordinate certain activities that they can’t carry out solo. In addition to sending out signals, cells have to receive information. To help them do this, they use molecular “ears” called receptors on their surfaces. When a chemical messenger attaches to a receptor, it tells the cell what’s going on and causes a response.

Scientists are following the dialogue, learning how cell signals affect health and disease. They’re also starting to take part in the cellular conversations, inserting their own comments with the goal of developing therapies that set a diseased system right.

Continue reading this new Inside Life Science article