Whether it’s a microscope, computer program or lab technique, technology is at the heart of biomedical research. Its central role is particularly clear from this month’s posts.

Some show how different tools led to basic discoveries with important health applications. For instance, a supercomputer unlocked the secrets of a drug-making enzyme, a software tool identified disease-causing variations among family members and high-powered microscopy revealed a mechanism allowing microtubules—and a cancer drug that targets them—to work.

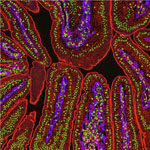

Another theme featured in several posts is novel uses for established technologies. The scientists behind the cool image put a new spin on a long-standing imaging technology to gain surprising insights into how some brain cells dispose of old parts. Similarly, the finding related to sepsis demonstrates yet another application of a standard lab technique called polymerase chain reaction: assessing the immune state of people with this serious medical condition.

“We need tools to answer questions,” says NIGMS’ Doug Sheeley, who oversees biomedical technology research resource grants. “When we find the answers, we ask new questions that then require new or improved tools. It’s a virtuous cycle that keeps science moving forward.”