Credit: Rhiju Das

Rhiju Das

Fields: Biophysics and biochemistry

Works at: Stanford University

Born and raised in: The greater Midwest (Texas, Indiana and Oklahoma)

Studied at: Harvard University, Stanford University

When he’s not in the lab he’s: Enjoying the California outdoors with his wife and 3-year-old daughter

If he could recommend one book about science to a lay reader, it would be: “The Eighth Day of Creation,” about the revolution in molecular biology in the 1940s and 50s.

At the turn of the 21st century, Rhiju Das saw a beautiful picture that changed his life. Then a student of particle physics with a focus on cosmology, he attended a lecture unveiling an image of the ribosome—the cellular machinery that assembles proteins in every living creature. Ribosomes are enormous, complicated machines made up of many proteins and nucleic acids similar to DNA. Deciphering the structure of a ribosome—the 3-D image Das saw—was such an impressive feat that the scientists who accomplished it won the 2009 Nobel Prize in chemistry.

Das, who had been looking for a way to apply his physics background to a research question he could study in a lab, had found his calling.

“It was an epiphany—it was just flabbergasting to me that a hundred thousand atoms could find their way into such a well-defined structure at atomic resolution. It was like miraculously a bunch of nuts and bolts had self-assembled into a Ferrari,” recounted Das. “That inspired me to drop everything and learn everything I could about nucleic acid structure.”

Das focuses on the nucleic acid known as RNA, which, in addition to forming part of the ribosome, plays many roles in the body. As is the case for most proteins, RNA folds into a 3-D shape that enables it to work properly.

Das is now the head of a lab at Stanford University that unravels how the structure and folding of RNA drives its function. He has taken a unique approach to uncovering the rules behind nucleic acid folding: harnessing the wisdom of the crowd.

Together with his collaborator, Adrien Treuille of Carnegie Mellon University, Das created an online, multiplayer video game called EteRNA  . More than a mere game, it does far more than entertain. With its tagline “Played by Humans, Scored by Nature,” it’s upending how scientists approach RNA structure discovery and design.

. More than a mere game, it does far more than entertain. With its tagline “Played by Humans, Scored by Nature,” it’s upending how scientists approach RNA structure discovery and design.

Das’ Findings

Treuille and Das launched EteRNA after working on another computer game called Foldit, which lets participants play with complex protein folding questions. Like Foldit, EteRNA asks players to assemble, twist and revise structures—this time of RNA—onscreen.

But EteRNA takes things a step further. Unlike Foldit, where the rewards are only game points, the winners of each round of EteRNA actually get to have their RNA designs synthesized in a wet lab at Stanford. Das and his colleagues then post the results—which designs resulted in a successful, functional RNAs and which didn’t—back online for the players to learn from.

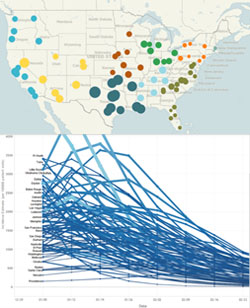

In a paper published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences  , Das and his colleagues showed how effective this approach could be. The collective effort of the EteRNA participants—which now number over 100,000—was better and faster than several established computer programs at solving RNA design problems, and even came up with successful new structural rules never before proposed by scientists or computers.

, Das and his colleagues showed how effective this approach could be. The collective effort of the EteRNA participants—which now number over 100,000—was better and faster than several established computer programs at solving RNA design problems, and even came up with successful new structural rules never before proposed by scientists or computers.

“What was surprising to me was their speed,” said Das. “I had just assumed that it would take a year or so before players were really able to analyze experimental data, make conclusions and come up with robust rules. But it was one of the really shocking moments of my life when, about 2 months in, we plotted the performance of players against computers and they were out-designing the computers.”

“As far as I can tell, none of the top players are academic scientists,” he added. “But if you talk to them, the first thing they’ll tell you is not how many points they have in the game but how many times they’ve had a design synthesized. They’re just excited about seeing whether or not their hypotheses were correct or falsified. So I think the top players truly are scientists—just not academic ones. They get a huge kick out of the scientific method, and they’re good at it.”

To capture lessons learned through the crowd-sourcing approach, Das and his colleagues incorporated successful rules and features into a new algorithm for RNA structure discovery, called EteRNABot, which has performed better than older computer algorithms.

“We thought that maybe the players would react badly [to EteRNABot], that they would think they were going to be automated out of existence,” said Das. “But, as it turned out, it was exciting for them to have their old ideas put into an algorithm so they could move on to the next problems.”

You can try EteRNA for yourself at http://eternagame.org  . Das and Treuille are always looking for new players and soliciting feedback.

. Das and Treuille are always looking for new players and soliciting feedback.