Mitochondria have proteins that span their membranes to control the flow of messages and materials moving into and out of the organelle. One way scientists can learn more about how membrane proteins function—and how medicines might interact with them—is to determine their structures. But for a variety of reasons, obtaining the structures has been notoriously difficult.

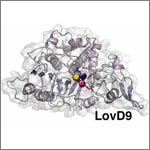

Two structural studies have now shed light on the mysterious mitochondrial membrane protein TSPO. This protein plays a key role in transporting cholesterol and drugs into the cell’s mitochondria. While here, the cholesterol is converted to steroid hormones that are essential for numerous bodily functions. Although many researchers have been studying TSPO since the 1990s, they’ve remained uncertain about its mechanisms and how it truly functions. Continue reading “Structural Studies Demystify Membrane Protein”