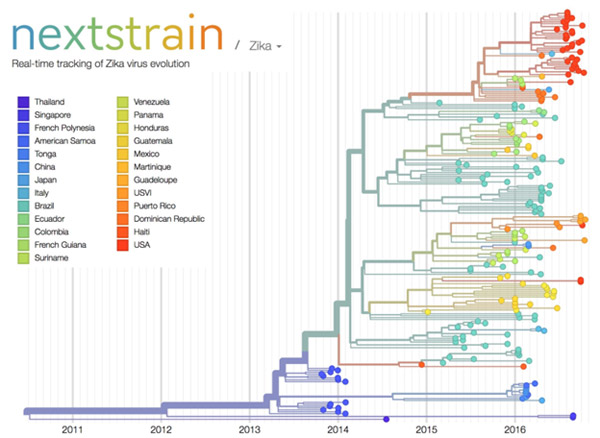

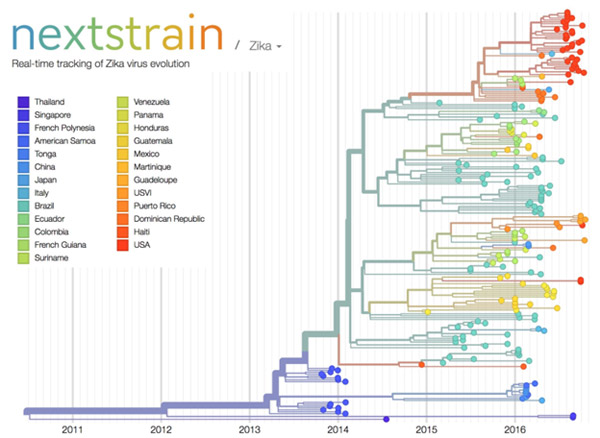

Credit: Trevor Bedford and Richard Neher, nextstrain.org.

Over the past decade, scientists and clinicians have eagerly deposited their burgeoning biomedical data into publicly accessible databases. However, a lack of computational tools for sharing and synthesizing the data has prevented this wealth of information from being fully utilized.

In an attempt to unleash the power of open-access data, the National Institutes of Health, in collaboration with the Howard Hughes Medical Institute and Britain’s Wellcome Trust, launched the Open Science Prize. Last week, after a multi-stage public voting process, the inaugural award was announced. The winner of the grand prize—and $230,000—is a prototype computational tool called nextstrain  that tracks the spread of emerging viruses such as Ebola and Zika. This tool could be especially valuable in revealing the transmission patterns and geographic spread of new outbreaks before vaccines are available, such as during the 2013-2016 Ebola epidemic and the current Zika epidemic.

that tracks the spread of emerging viruses such as Ebola and Zika. This tool could be especially valuable in revealing the transmission patterns and geographic spread of new outbreaks before vaccines are available, such as during the 2013-2016 Ebola epidemic and the current Zika epidemic.

An international team of scientists—led by NIGMS grantee Trevor Bedford of the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle, and Richard Neher  of Biozentrum at the University of Basel, Switzerland—developed nextstrain as an open-access system capable of sharing and analyzing viral genomes. The system mines viral genome sequence data that researchers have made publicly available online. nextstrain then rapidly determines the evolutionary relationships among all the viruses in its database and displays the results of its analyses on an interactive public website.

of Biozentrum at the University of Basel, Switzerland—developed nextstrain as an open-access system capable of sharing and analyzing viral genomes. The system mines viral genome sequence data that researchers have made publicly available online. nextstrain then rapidly determines the evolutionary relationships among all the viruses in its database and displays the results of its analyses on an interactive public website.

The image here shows nextstrain’s analysis of the genomes from Zika virus obtained in 25 countries over the past few years. Plotting the relatedness of these viral strains on a timeline provides investigators a sense of how the virus has spread and evolved, and which strains are genetically similar. Researchers can upload genome sequences of newly discovered viral strains—in this case Zika—and find out in short order how their new strain relates to previously discovered strains, which could potentially impact treatment decisions.

Nearly 100 interdisciplinary teams comprising 450 innovators from 45 nations competed for the Open Science Prize. More than 3,500 people from six continents voted online for the winner. Other finalists for the prize focused on brain maps, gene discovery, air-quality monitoring, neuroimaging and drug discovery.

nextstrain was funded in part by NIH under grant U54GM111274.