Shanta Dhar

Fields: Chemistry and cancer immunotherapy

Works at: University of Georgia, Athens

Born and raised in: Northern India

Studied at: Indian Institute of Science, Bangalore; Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, Md.; and Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, Mass.

To unwind: She hits the gym

Credit: Frankie Wylie, Stylized Portraiture

The human body is, at its most basic level, a giant collection of chemicals. Finding ways to direct the actions of those chemicals can lead to new treatments for human diseases.

Shanta Dhar, an assistant professor of chemistry at the University of Georgia, Athens (UGA), saw this potential when she was exposed to the field of cancer immunotherapy as a postdoctoral researcher at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. (Broadly, cancer immunotherapy aims to direct the body’s natural immune response to kill cancer cells.) Dhar was fascinated by the idea and has pursued research in this area ever since. “I always wanted to use my chemistry for something that could be useful [in the clinic] down the line,” she said.

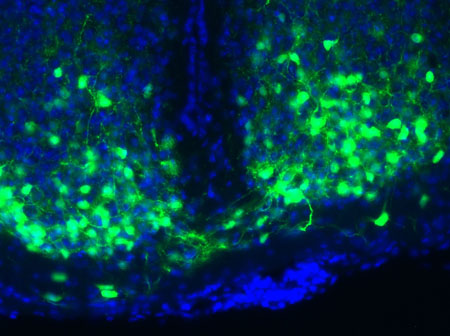

A major challenge in the field has been training the body’s immune system—specifically the T cells—to recognize and attack cancer cells. The process of training T cells to go after cancer is rather like training a rescue dog to find a lost person: First, you present the scent, then you command pursuit.

The type of immune cell chiefly responsible for training T cells to search for and destroy cancer is a called a dendritic cell. First, dendritic cells present T cells with the “scent” of cancer (proteins from a cancer cell). Then they activate the T cells using signaling molecules.

Dhar’s Findings

Dhar’s work focuses on creating the perfect trigger for cancer immunotherapy—one that would provide both the scent of cancer for T cells to recognize and a burst of immune signaling to activate the cells.

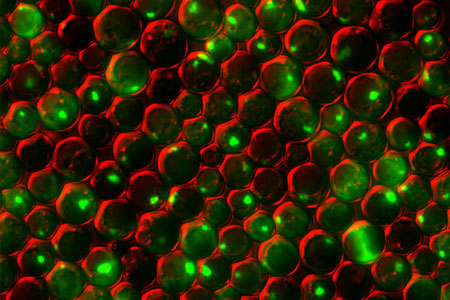

Using cells grown in the lab, Dhar’s team recently showed that they could kill most breast cancer cells using a new nanotechnology technique, then train T cells to eradicate the remaining cancer cells.

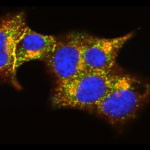

For the initial attack, the researchers used light-activated nanoparticles that target mitochondria in cancer cells. Mitochondria are the organelles that provide cellular energy. Their destruction sets off a signaling cascade that triggers dendritic cells to produce one of the proteins needed to activate T cells.

Because the strategy worked in laboratory cells, Dhar and her colleague Donald Harn of the UGA infectious diseases department are now testing it in a mouse model of breast cancer to see if it is similarly effective in a living organism.

For some reason, the approach works against breast cancer cells but not against cervical cancer cells. So the team is examining the nanoparticle technique to see if they can make it broadly applicable against other cancer types.

Someday, Dhar hopes to translate this work into a personalized cancer vaccine. To create such a vaccine, scientists would remove cancer cells from a patient’s body during surgery. Next, in a laboratory dish, they would train immune cells from the patient to kill the cancer cells, then inject the trained immune cells back into the patient’s body. If the strategy worked, the trained cells would alert and activate T cells to eliminate the cancer.