Much as a photographer brings distant objects into focus with a telephoto lens, scientists can now see previously indistinct cellular components as small as a few billionths of a meter (nanometers). By overcoming some of the limitations of conventional optical microscopy, a set of techniques known as super-resolution fluorescence microscopy has changed once-blurry images of the nanoworld into well-resolved portraits of cellular architecture, with details never seen before in biology. Reflecting its importance, super-resolution microscopy was recognized with the 2014 Nobel Prize in chemistry.

Using the new techniques, scientists can observe processes in living cells across space and time and study the movements, interactions and roles of individual molecules. For instance, they can identify and track the proteins that allow a virus to invade a cell or those that enable tumor cells to migrate to distant parts of the body in metastatic cancer. The ability to analyze individual molecules, rather than collections of molecules, allows scientists to answer longstanding questions about cellular mechanisms and behavior, such as how cells move along a surface or how certain proteins interact with DNA to regulate gene activity.

How Super-Resolution Works

The development of super-resolution fluorescence microscopy resulted from several major discoveries that, when combined, have allowed scientists to produce high-resolution images. One of these discoveries was the observation that certain fluorescent proteins could be turned off and then on again at will using different wavelengths of light. Such photoswitchable fluorescent probes are used to tag individual proteins or DNA molecules in a biological sample.

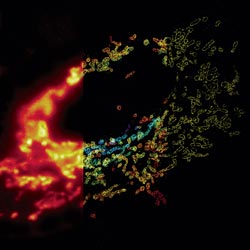

Scientists have developed numerous super-resolution techniques. In methods such as PALM (photoactivated localization microscopy) and STORM (stochastic optical reconstruction microscopy), the glow from the fluorescent proteins is toggled on and off a few molecules at a time, stimulated by a laser at a precise wavelength. The microscope takes a picture of the glowing tags and then fires another shot of laser light. These methods require that the activated proteins be far enough apart that the fluorescence they emit is not overlapping. By repeating the process hundreds of times and then superimposing the resulting images, scientists can create a higher-resolution picture than was possible with conventional optical microscopy.

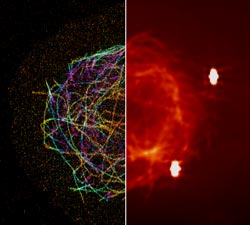

Another method, called STED (stimulated emission depletion), achieves high resolution through a different process. In STED, one laser beam stimulates fluorescence in tagged biomolecules. A second, overlapping doughnut-shaped laser beam turns off that fluorescence in all but a nanometer-sized area in the center. By scanning across a sample with the two beams, scientists can build an image with nanometer-scale resolution.

Although some challenges remain, such as capturing precise images of cellular components in motion and eliminating optical aberrations caused by the deep three-dimensional environment of the cell, super-resolution techniques are revolutionizing our understanding of cell biology.