Has the “spring forward” time change left you feeling drowsy? While researchers can’t give you back your lost ZZZs, they are unraveling a long-standing mystery about sleep. Their work will advance the scientific understanding of the process and could improve ways to foster natural sleep patterns in people with sleep disorders.

Working at Massachusetts General Hospital and MIT, Christa Van Dort, Matthew Wilson, and Emery Brown focused on the stage of sleep known as REM. Our most vivid dreams occur during this period, as do rapid eye movements, for which the state is named. Many scientists also believe REM is crucial for learning and memory.

REM occurs several times throughout the night, interspersed with other sleep states collectively called non-REM sleep. Although REM is clearly necessary—it occurs in all land mammals and birds—researchers don’t really know why. They also don’t understand how the brain turns REM on and off.

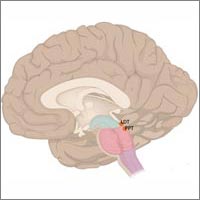

In their quest to understand how the brain regulates REM, the Massachusetts team focused on areas in the brain stem known to play a role in REM. These areas, abbreviated LDT (for laterodorsal tegmentum) and PPT (for pedunculopontine tegmentum), contain different neurons distinguished by the type of chemical messages, or neurotransmitters, they use to communicate.

Sorting out the functions of intermingled neurons is like trying to understand simultaneous conversations in a crowded, multilingual café. To figure out which neurons control REM in the mouse LDT and PPT, the researchers isolated just one conversation—the one spoken using the neurotransmitter acetylcholine.

With genetic and imaging techniques, the scientists selected and lit up only the acetylcholine-speaking (cholinergic) neurons. Neighboring neurons that conversed in any other neurotransmitter language remained dark.

The research team was able to activate the cholinergic neurons by shining blue laser light on either of the two brainstem areas. In many cases, doing so would move sleeping mice from non-REM to REM. The scientists noticed that activating cholinergic neurons increased the number of REM sleep episodes, but didn’t make episodes last longer. They concluded that cholinergic neurons in the LDT and PPT are important to trigger REM, but not to maintain it, which must be the job of other neurons or a different region of the brain.

Next, the scientists plan to study how cholinergic neurons communicate with other systems in the brain and the role they play in regulating non-REM sleep. The researchers may also investigate the function of the other neurons in the LDT and PPT, namely those that communicate using the neurotransmitters glutamate or GABA.

Now, every time you spring forward or fall back, you can ponder all the amazing things your brain does each night when you’re asleep—and think about the researchers working to puzzle it all out.

This research was funded in part by NIH under grants R01GM104948, DP1OD003646 and T32HL007901.

This is why tricyclics impact cataplexy in narcolepsy?