If you participated in a cupcake taste test, do you think you’d be able to distinguish a treat made with natural sugar from one made with artificial sweetener? Scientists have known for decades that animals can tell the difference, but what’s been less clear is how.

Now, researchers at the New York University School of Medicine have identified a collection of specialized nerve cells in fruit flies that acts as a nutrient-detecting sensor, helping them select natural sugar over artificial sweetener to get the energy they need to survive.

“How specific sensory stimuli trigger specific behaviors is a big research question,” says NIGMS’ Mike Sesma. “Food preferences involve more than taste and hunger, and this study, which was done in an organism with many of the same cellular components as humans, gives us a glimpse of the complex interplay among the many factors.”

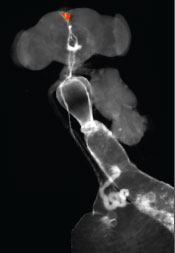

The study, described in the July 15 issue of Neuron, builds on the researchers’ earlier studies of feeding behavior that showed hungry fruit flies, even ones lacking the ability to taste, selected calorie-packed sugars over zero-calorie alternatives. The scientists, led by Greg Suh and Monica Dus ![]() , suspected that the flies had a molecular system for choosing energy-replenishing foods, especially during periods of starvation.

, suspected that the flies had a molecular system for choosing energy-replenishing foods, especially during periods of starvation.

To identify the sensor, Suh, Dus (now at the University of Michigan) and others looked for neurons in the fly brain that responded differently after flies ate natural or artificial sugars. The search led them to six neurons, collectively called Dh44. These neurons produce a hormone that’s similar to a mammalian one involved in regulating stress responses and maintaining energy balances.

The researchers observed that when the flies consumed the caloric sugar—but not when they ate the artificial sweetener—the Dh44 neurons fired and released the hormone. This activation by nutritive sugars promoted digestion and, at the same time, stimulated feeding. This input-output cycle is called a feedback loop.

The researchers are now wondering if the mammalian hormone similar to the Dh44 one is part of a nutrient sensor system. Suh and others involved in the work plan to investigate this question in mice.

This work was funded in part by NIH grants R01GM089746, R00DK097141 and R01DC001279.