A new study has added another twist to the CRISPR story. As we’ve highlighted in several recent posts, CRISPR is an immune system in bacteria that recognizes and destroys viral DNA and other invading DNA elements, such as transposons. Scientists have adapted CRISPR into an indispensable gene-editing tool now widely used in both basic and applied research.

Many previously described CRISPR systems detect and cut viral DNA, insert the DNA pieces into the bacterial genome and then use them as molecular “mug shots” to flag and destroy the virus if it attacks again. But various viruses use RNA, not DNA, as genetic material. Although research has shown that some CRISPR systems also can target RNA, how these systems can archive harmful RNA encounters in the bacterial genome was unknown.

To help address this question, an international team of scientists set out to determine whether some bacteria use a CRISPR system to spot invading RNAs and store a memory of the invasion event in the bacterial genome. The researchers followed one important clue: Several bacteria have a version of the Cas1 CRISPR protein that’s fused to reverse transcriptase, a protein that can make DNA from RNA.

Sukrit Silas, a graduate student in the lab of Andrew Fire at Stanford University, wanted to find out what these gene fusions might do. She assembled a research team by reaching out to Georg Mohr, a scientist in the lab of Alan Lambowitz at the University of Texas-Austin who has expertise in analyzing proteins that act on RNA.

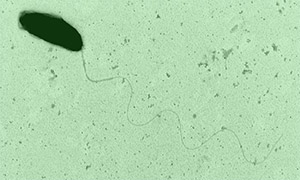

As reported in their study published in the journal Science, the team used Marinomonas mediterranea, a marine bacterium that has the Cas1-reverse transcriptase fusion and is easy to grow in the lab.

The researchers confirmed that the protein fusion can take DNA mug shots from RNA. The Cas1 enzyme then adds this molecular information to the bacterial genome via a new biochemical mechanism the study also uncovered. The researchers think that this CRISPR variant might help bacterial cells fight viruses that use RNA instead of DNA or to remove RNAs whose expression is unwanted or harmful to the cell.

The researchers also noted that some other bacteria have the genes for the reverse transcriptase and CRISPR enzymes sitting next to one another instead of fused together as in M. mediterranea. This finding suggests that RNA-eliminating CRISPR systems might be common among bacteria.

The new RNA-based CRISPR mechanism could have applications in a range of industries. For example, scientists might one day insert an RNA-targeting CRISPR to detect and exterminate viruses that infect bacteria used in making cheeses or yogurts. It also could potentially play a role in biomedicine as warning and defense systems against RNA viruses such as HIV, hepatitis C, influenza and other RNA viruses.

This work was funded in part by NIH under grants R01GM37706, R01GM37949 and R01GM37951.