Your immune system is on patrol every day. It protects your body from bacteria, viruses, and other germs. But if something goes wrong, it can also cause big problems.

Sepsis happens when your body’s response to an infection spirals out of control. Your body releases molecules into the blood called cytokines to fight the infection. But those molecules then trigger a chain reaction.

“Sepsis is basically a life-threatening infection that leads to organ dysfunction,” says Richard Hotchkiss, M.D., who studies sepsis at Washington University in St. Louis, Missouri. The most dangerous stage of sepsis is called septic shock. It can cause multiple organs to fail, including the liver, lungs, and kidneys.

Septic shock begins when the body’s response to an infection damages blood vessels. When blood vessels are damaged, your blood pressure can drop very low. Without normal blood flow, your body can’t get enough oxygen.

Almost 1.7 million people in the U.S. develop sepsis every year. Even with modern treatments, it still kills nearly 270,000 Americans. Many recover. Some have lifelong damage to the body and brain.

“We can get many people over that first infection that caused the sepsis,” Dr. Hotchkiss explains. “But then they’re at risk of dying from a second infection because of their weakened condition.”

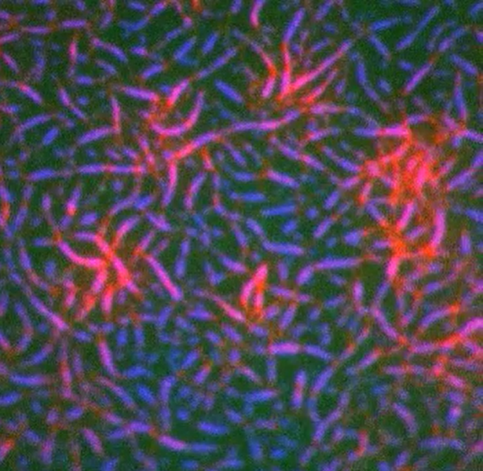

Bacterial infections cause most sepsis cases. But sepsis can also result from other infections, including viral infections, such as COVID-19 or the flu (influenza).

Anyone can get sepsis. But certain people are at higher risk, including infants, children, and older adults.

The early symptoms of sepsis are similar to those of many other conditions. These can include fever, chills, rapid breathing or heart rate, a skin rash, confusion, and disorientation.

It’s important to know the symptoms. Sepsis is a medical emergency. If you or your loved one has an infection that isn’t getting better or is getting worse, get medical care immediately.

Get Ahead of Sepsis

- Prevent infections. Take good care of chronic conditions. Get recommended vaccines.

- Practice good hygiene. Wash your hands. Keep cuts clean and covered until healed.

- Know the symptoms. Pay attention to symptoms that can include any one or a combination of: confusion, disorientation, shortness of breath, rapid heart rate, fever, shivering, chills, extreme pain, and clammy or sweaty skin.

- Act fast. Get medical care immediately if you suspect sepsis or have an infection that isn’t getting better or is getting worse.

Adapted from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Researchers are now looking for better ways to diagnose sepsis. One strategy is to use artificial intelligence to predict a patient’s risk of sepsis when they have an infection.

There are few medicines that help treat sepsis. Doctors try to stop the infection and support the functions of vital organs. This usually includes giving oxygen and fluids.

Dr. Hotchkiss and other researchers are exploring new treatments for the condition. His team has been testing ways to measure which immune cells are affected by sepsis.

The traditional understanding of sepsis, he says, is that the body responds too strongly to an infection. But his group has found that the body also produces too few of some important types of immune cells. This makes it hard to effectively fight the infection that first triggered sepsis. It can also cause a lot of collateral damage and make a person more vulnerable to other infections.

Dr. Hotchkiss’s team is now testing ways to boost the immune cells that are vital for fighting infections using drugs. They’ve found they can increase these cells in patients with sepsis. Next, they will be testing whether this new approach can improve survival.

To learn more about sepsis, see our Sepsis fact sheet.

Dr. Hotchkiss’s research is supported by NIGMS grant R35GM126928.