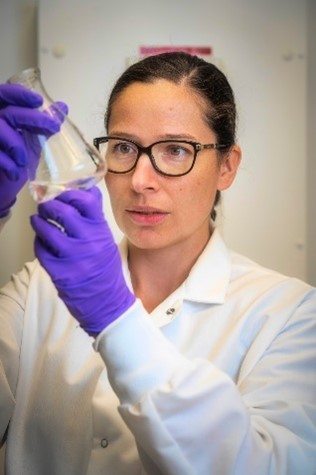

“As a researcher, you get to learn something new every day, and that knowledge feeds more questions. It’s this eternal learning process, and I find that really enticing about being in science,” says Eszter Boros, Ph.D., an assistant professor of chemistry at Stony Brook University in Stony Brook, New York. Our interview with Dr. Boros highlights her journey of becoming a scientist and her research on biomedical applications of metals.

Q: What drew you to science?

A: I was born and raised in Switzerland, and I went to a linguistics-focused high school there, but I gravitated to chemistry because I loved that we could understand the world at a molecular level and see the macroscopic consequences of microscopic processes.

Q: How did you become a scientist?

A: I went to college at the University of Zurich and majored in chemistry. I had a life-changing moment when one of my professors, Dr. Roger Alberto, talked about the cancer drug cisplatin. It blew my mind that this small molecule with a metal in it was being used to combat cancer, and I decided to learn more about metal ions and how we can use them for biomedical applications. Dr. Alberto became my research advisor for undergrad, and in his lab, I learned about radioactive metal ions and isotopes and how they can be used to diagnose and treat diseases.

I started to think about graduate school, since it was the way to do more research, which I liked a lot. I realized that all the papers I was reading were in English, so I wanted to go to North America to pursue a Ph.D. Dr. Alberto recommended scientists whom I could work with, and one of them, Dr. Chris Orvig, ended up being my Ph.D. advisor at the University of British Columbia. In his lab, I studied metal ions that had radioactive isotopes.

Q: What were the next steps in your career?

A: As I got close to graduating, I realized that I could do inorganic chemistry with these metal ions, but I didn’t understand much about how to move a radiopharmaceutical—or a radioactive

drug—from design to testing and use, and I wanted to learn more. At a conference, I met Dr. Peter Caravan, who was developing MRI contrast agents—metal-based compounds used to help visualize internal parts of the body during scans. I ended up doing a postdoc in his lab at Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School. I was part of the whole process of coming up with a molecule, making it, and then testing it in a research organism of disease.

About 2 years in, Dr. Caravan and I decided that I would be a good candidate for a K99/R00 grant. My first and second applications weren’t successful, but the third was. I continued doing research in Dr. Caravan’s lab for another 2 years after I got my K99/R00 from the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering (NIBIB). When I started my faculty search, I was looking for chemistry departments that had close affiliations with medical schools, and that’s how I ended up starting my own research program at Stony Brook in 2017.

Q: What do you research in your lab?

A: My lab is interested in understanding what happens when there’s too much or too little of a metal in a biological system and what health implications result from that. My team additionally studies the use of metals for diagnostics and therapies. We have three large research pillars. The first pillar looks at metal ions with interesting optical properties for use as medical imaging agents.

The second pillar is better understanding the chemistry of metal ions with interesting radioactive isotopes that we can use as radiopharmaceuticals. We develop chemistry that selectively captures these metal ions so they can be delivered to tissues of interest, predominantly for cancer applications. Then we validate the molecules in cells and mice.

The third pillar is looking at means to deliver metal ions to bacteria and selectively kill them. This is the work funded by my NIGMS Maximizing Investigators’ Research Award, which I received in 2021. A lot of bacteria are starting to develop resistance to conventional antibiotics, and that’s what got us interested in this project. So far, we’ve mainly explored the metal gallium, and when we delivered gallium-linked antibiotics to a mouse infected with bacteria, it led to more efficient killing of the bacteria than just the antibiotic alone.

Q: What challenges have you faced in your career path?

A: It’s a big challenge to be an international student in a Ph.D. program—not just because grad school is hard but also because your family is very far away. There was a 9-hour time difference between my family and me, so even calling them was something I had to schedule, and flying home was a 17-hour ordeal. It took a lot of resilience to not just want to go home because I missed my family.

I also think the transition from being a trainee to being a mentor is a challenging one, and it’s something that I continue to learn about. I feel like you’re never finished on this trajectory of becoming a better mentor, but it’s an enjoyable challenge.

Q: What do you consider your biggest accomplishment so far?

A: I’m very proud that I was able to build a research program that people want to be part of. I get to recruit students and postdocs who want to help me answer research questions, and it’s incredibly gratifying to share the joy of discovery.

Dr. Boros’ research is supported by NIGMS grant R35GM142770 and NIBIB grant R21EB030071.