“An important part of being in science is being in a community,” says Neil Garg, Ph.D., Distinguished Professor and chair of the department of chemistry and biochemistry at the University of California Los Angeles (UCLA). That philosophy has led him to prioritize mentorship, diversity, and inclusion—while maintaining research excellence—as well as re-envisioning what it means to educate students and the public.

Falling in Love With Chemistry

Science was always a part of Dr. Garg’s childhood. He participated in science fairs as a kid but says he did it for the community and not necessarily for the love of science. “When I look back on those projects, they were always with friends—never by myself,” he says. His parents were both scientists and strongly encouraged him to go into medicine, and although he became a premed major at New York University (NYU), he ultimately chose a different path.

During his freshmen honors chemistry class, Dr. Garg questioned whether he was cut out for chemistry and even tried to drop the class, but he ultimately stayed in the course and even began doing research with professor Marc Walters, Ph.D. He says, “For the first time I recognized that I enjoyed chemistry and that I was good enough to do it.” In later chemistry courses, he found the community he’d loved as a kid: “My organic chemistry professor, Yorke Rhodes, Ph.D., enforced that chemistry was critical thinking and reasoning, not memorization. His excitement got us working in groups and building intellectual stimulation and support.” Dr. Garg went on to earn his Ph.D. from the California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, in the lab of Brian Stoltz, Ph.D.

Dr. Garg began considering postdoctoral positions and mentors. He recalls, “I thought about branching out from synthetic chemistry, but I couldn’t get as excited about other areas of chemistry as I was about making complex molecules. I also knew I wanted an awesome mentor and a great work environment, so I joined the lab of Larry Overman, Ph.D., at the University of California Irvine.” Dr. Overman emphasized the importance of effective mentoring and lifelong learning and encouraged Dr. Garg to apply for the NIGMS Pathway to Independence Award, which funds part of a researcher’s postdoctoral training and up to 3 years of their independent career with a major focus on mentorship. He received the award and soon transitioned into his independent career as a UCLA faculty member.

Educating Unconventionally

At first, Dr. Garg was only teaching graduate-level chemistry courses at UCLA, but when the opportunity arose to teach organic chemistry to undergraduates majoring in life sciences, he took it—and soon transformed the class into one of the most popular on campus. After a rough first few days, he was able to connect with and engage his students, who were rowdy, energetic, and excited. He created an unconventional extra credit assignment where the students made music videos about organic chemistry and even gave them difficult synthetic chemistry problems to solve—and they embraced both challenges. “The students are the innovators: Whether they’re solving a complex synthesis problem or making music videos, they can do really cool things,” he says. “It opened my eyes to the idea that we could be educating in broader ways, not just using the textbook model.”

Student-led innovation has been a driving principle for Dr. Garg. He has helped different groups of students bring their out-of-the-box ideas to life, including:

- Backside Attack, an iOS app to help students learn organic chemistry

- ChemMatch.net, a flashcard-style game to test chemistry knowledge in an engaging way

- QRChem.net, a website to view almost any molecule in 3D and interact with it on a smartphone

Another innovative education idea came not from his students but from his kids. One night his daughter refused to eat her hot dog because “it had chemicals in it.” At first Dr. Garg was stunned that she—the 4-year-old daughter of an organic chemist—thought chemicals were bad, but then he saw the teaching potential. He started pulling up chemical structures to show her, and they talked about ice cream, candy, and sucrose. He made it into a game, realizing his kids loved chemistry but just didn’t know it yet. He worked with his daughters to eventually create a chemistry coloring book for kids. “They’re getting more than just the kids involved in chemistry. The parents often have no idea what these common chemicals are until they see them drawn out—mostly just carbon, nitrogen, and oxygen connected in different ways,” he says.

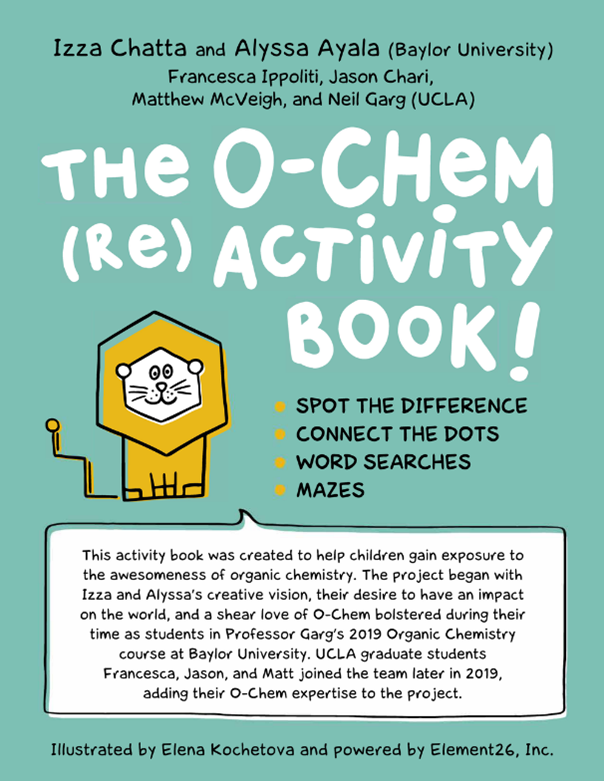

Since publishing the first coloring book, some of the students in his lab decided to translate it into Spanish, and he and his daughters created a follow-up book about medicines. After winning the prestigious Robert Foster Cherry Award for Great Teaching, Dr. Garg spent a semester teaching at Baylor University in Waco, Texas, where he helped a group of Baylor students, in collaboration with UCLA students, develop an activity book all about organic chemistry—The O-Chem (Re)Activity Book. He sums up his unconventional education projects with this: “Why can’t we innovate when we think about educating the public?”

Being a Mentor and a Researcher

Beyond outreach and education, Dr. Garg researches fundamental and applied aspects of organic chemistry. His lab works with molecules that have classically been deemed either unreactive or too reactive—which are both “synthetically useless,” as he puts it—and finds ways to make them chemically useful. Using what they learn during that process, the lab team builds complex structures, leading to some of the lab’s applied chemistry work in the areas of medicinal and materials chemistry. For example, they’ve created electrochemistry technology that’s being developed to detect marijuana drug levels.

Finding Balance With Fatherhood

Despite Dr. Garg’s busy profession, he’s very involved in his four kids’ lives. “Many people fear a consequence of academia is that they can’t live a balanced life,” he says. “There’s never enough time, but it’s all about priorities and how we choose them.” He chaperones his kids’ fieldtrips, volunteers at local schools, and currently serves as the room parent for one of his children’s classes. He and members from his lab also volunteer in the classrooms.

From the start of his research group, Dr. Garg has emphasized creating a diverse and inclusive space where everyone is respected. Women typically make up half of his research group, and he’s proud that he’s been able to recruit students of different backgrounds to work in his lab. “We don’t have a culture driven by hours and number of reactions,” he says. “We talk about students’ projects, individual goals, and long-term career aspirations rather than counting experiments. That spirit of the lab drives the types of students we recruit.” He takes his role as a mentor seriously and encourages others to do the same through an initiative he co-founded with Jen Heemstra, Ph.D., called #MentorFirst that emphasizes the importance of mentorship in research.

Dr. Garg says his lab is a “heavy feedback zone” where everyone works as a team and respects one another. When new people join his lab, he reminds them: “You need to have an open attitude, be kind to others, and try to learn everything you can.” When reflecting on his biggest accomplishment as a scientist so far, he says, “Any small amount of credit I can take for educating all these amazing people—that’s what it’s all about. They challenge conventional thinking and are going out into the world to contribute that to society.”

Dr. Garg’s research is funded by NIGMS grant R35GM139593.