The average human brain is only about 3 pounds, but this complex organ punches well above its weight, acting as the control center for the whole body. Many of the brain’s intricacies still aren’t fully understood. To gain more insight into brain processes, scientists often peer into the brains of research organisms such as fruit flies and mice. These organisms have shed light on how our brains maintain circadian rhythms, how neuropsychiatric disorders develop, and more.

Here, we feature images and videos that NIGMS-supported researchers have created while investigating the secrets of the brain in research organisms. Visit our image and video gallery for more eye-catching scientific photos, illustrations, and videos.

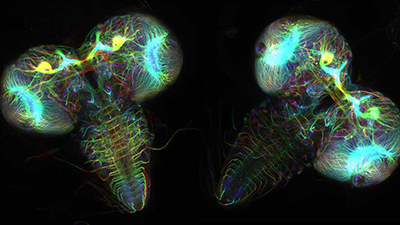

This image shows two fruit fly (Drosophila melanogaster) larvae brains with nerve cells, also called neurons, expressing tubulin protein tagged with fluorescent dye. Tubulin makes up strong, hollow fibers called microtubules that play important roles in nerve cell growth and migration during brain development.

The green spots in this mouse brain are cells labeled with “calling cards,” a technology that records molecular events in brain cells as they mature. Understanding these processes during healthy development can guide further research into what goes wrong in cases of neuropsychiatric disorders. Also fluorescently labeled in this video are nerve cells (red) and nuclei (blue).

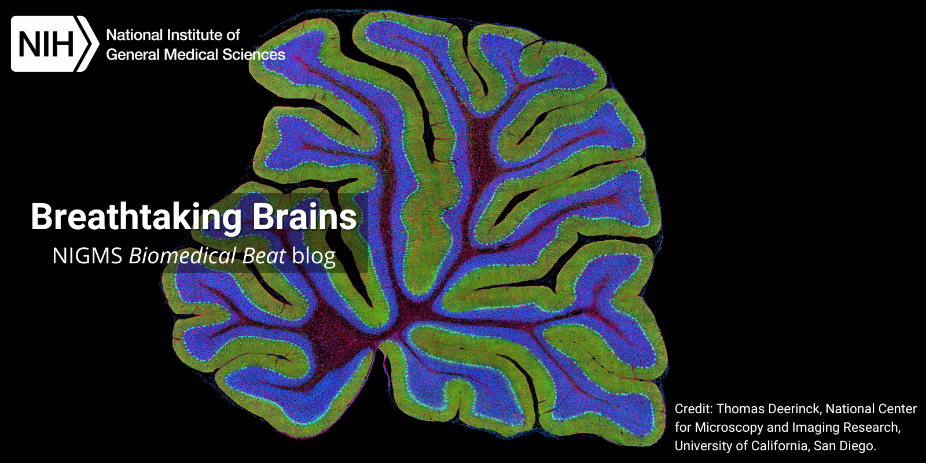

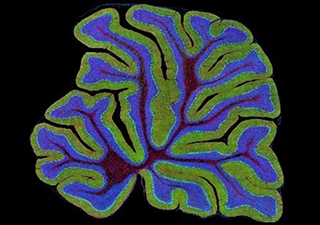

A mouse cerebellum is shown here in cross-section. The cerebellum controls movement. It’s found at the base of the brain and is made up of a single layer of tissue with deep folds like an accordion. Organisms with damage to the cerebellum often have difficulty with balance, coordination, and fine motor skills.

Each colored region in this adult fruit fly brain represents a group of nerve cells derived from a single stem cell. Roughly 100 stem cells are involved in building a fruit fly brain. Creating this video required fluorescently staining and imaging cells in thousands of fruit flies.

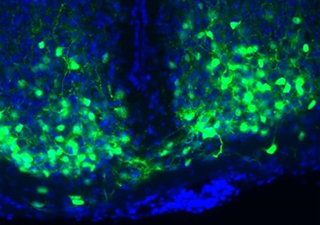

The mouse brain region in this image houses time-keeping nerve cells, shown in blue, and serves as a “master clock.” A small molecule called VIP, shown in green, enables the nerve cells to synchronize—or work in sync.