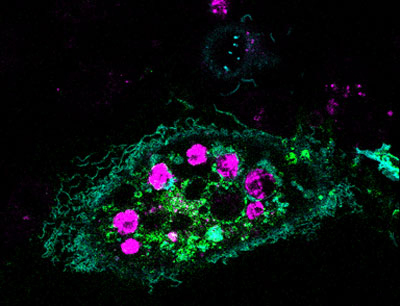

Credit: Cynthia Brodoway, Nemours/Alfred I. duPont

Hospital for Children

Alfred Atanda Jr.

Fields: Pediatric orthopedic surgery, sports medicine

Works at: Nemours/Alfred I. duPont Hospital for Children

Blogs: as Philly.com’s Sports Doc at

http://bit.ly/sportsdoc  Family fact

Family fact: Youngest of seven children

Musical skills: Piano and trumpet

Kitchen talent: Baking chocolate desserts for his pediatrician wife and their two young children

As a kid, Alfred Atanda loved science, sports and tinkering. He dreamed of being a construction worker or an engineer. Today, he works on one of the most complex construction projects of all: the human body.

As a pediatric orthopedic surgeon, Atanda focuses on sports medicine and injuries to children. He has a special passion for young baseball pitchers who have torn the ulnar collateral ligament (UCL) in the elbow of their throwing arm.

This sort of injury is most often caused by overuse. Many small tears accumulate over a long period, resulting in pain and slower, less accurate pitches. Decades ago, this sort of damage occurred almost exclusively in elite athletes. Now, Atanda sees it in children as young as 12 years old. He aims not only to study and treat these injuries, but also to find ways to prevent them.

His Findings

Atanda was first introduced to research on UCL injuries while working alongside team physicians for the Phillies, the professional baseball team in Philadelphia. The physicians wanted to determine whether ultrasound imaging could detect early warning signs—slight anatomical changes in the ligament—before the damage became severe enough to warrant an operation known as Tommy John surgery.

The research focused on Phillies pitchers who had no pain or other symptoms of injury. The multi-year project showed that the UCL in the throwing elbows of these players got progressively thicker and weaker compared to the same ligament in the players’ nonthrowing elbows. The scientists concluded that these physical changes are caused by prolonged exposure to professional-level pitching.

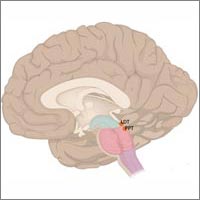

Atanda examines the elbow of a young patient. Courtesy: Cynthia Brodoway, Nemours/Alfred I. duPont Hospital for Children

Atanda wondered whether ultrasound imaging could also detect early signs of UCL damage in young pitchers—those in Little League through high school. There has been a dramatic rise in the number of young pitchers who are experiencing the same injuries and undergoing the same surgery as the pros.

Atanda secured funding for this project from an Institutional Development Award (IDeA). The IDeA program builds research capacities in states like Delaware, where Atanda works, that historically have received low levels of funding from the National Institutes of Health.

Atanda’s project began about a year ago, and has examined 55 young athletes so far.

“We found similar results to what we found with the Phillies,” Atanda says, indicating that the UCL in the throwing elbows of young athletes was noticeably thicker than the UCL in the nonthrowing elbows. And the damage seems progressive, he says: “We saw that these ligaments got thicker as the pitchers got older and had more pitching experience.”

The immediate goal of this project, which he hopes to continue for another 3 years, is prophylaxis. “We’re trying to prevent any kind of overuse elbow injuries and the need for Tommy John surgeries later on,” Atanda says. He also hopes to establish quantitative correlations between pitching behavior and anatomical changes.

Atanda also has longer-term aspirations. “My goal is to change the culture in sports for young athletes in general,” he says. “I want to show there are downsides to pitching so much.”

In addition to championing pitch count limits recommended by the American Sports Medicine Institute, Atanda advises a focus away from excess competition and toward getting exercise, enjoying social interaction, building self-confidence and having fun.

Atanda’s research is funded by the National Institutes of Health through grant P20GM103464

Content adapted from the NIGMS Findings magazine article Game Changer