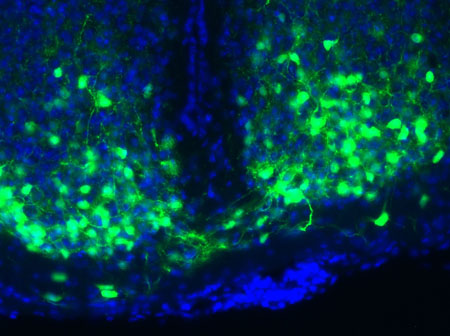

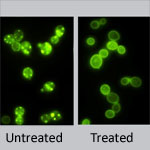

Many microorganisms can sense whether it’s day or night and adjust their activity accordingly. In tiny blue-green algae, the “quartz-crystal” of the time-keeping circadian clock consists of only three proteins, making it the simplest clock found in nature. Researchers led by Carl Johnson of Vanderbilt University recently found that, by manipulating these clock proteins, they could lock the algae into continuously expressing its daytime genes, even during the nighttime.

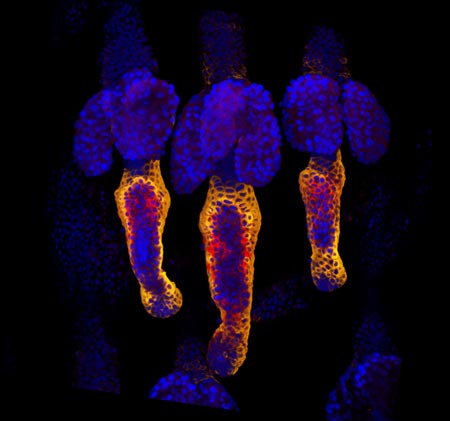

Why would one want algae to act like it’s always daytime? The kind used in Johnson’s study is widely harnessed to produce commercial products, from drugs to biofuels. But even when grown in constant light, algae with a normal circadian clock typically decrease production of biomolecules when nighttime genes are expressed. When the researchers grew the algae with the daytime genes locked “on” in constant light, the microorganism’s output increased by as much as 700 percent. This proof of concept experiment may be applicable to improving the commercial production of compounds such as insulin and some anti-cancer drugs.

Learn more:

Vanderbilt University Press Release

Johnson Laboratory

Circadian Rhythms Fact Sheet