Inside our bodies is a surprising amount of metal. Not enough to set off the scanners at the airport or make us rich, but enough to fill each of our cells with billions of metal ions, including calcium, iron, copper and zinc. These ions facilitate critical biological functions.

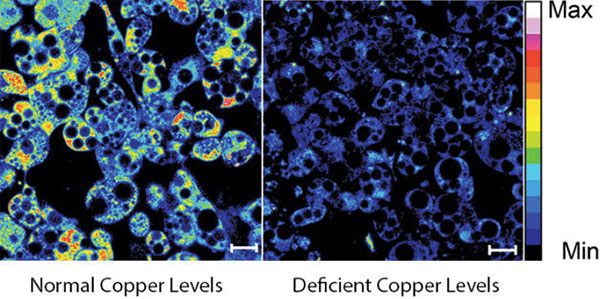

However, too much of any metal can be toxic, while too little can cause disease. Our cells carefully monitor and control their metal content using a whole series of proteins that bind, sense and transport metal ions.

Keeping tabs on why and how metals flow into and out of our cells is a passion of Thomas O’Halloran ![]() , professor of chemistry and molecular biosciences at Northwestern University in Illinois. For the past three decades, O’Halloran has investigated how fluctuations in the amount of metal ions inside cells influence gene expression, cell growth and other vital functions. Using a variety of approaches, he has uncovered new types of proteins that bind metal ions and investigated the role that imbalances in these ions play in a number of disease-related physiological processes.

, professor of chemistry and molecular biosciences at Northwestern University in Illinois. For the past three decades, O’Halloran has investigated how fluctuations in the amount of metal ions inside cells influence gene expression, cell growth and other vital functions. Using a variety of approaches, he has uncovered new types of proteins that bind metal ions and investigated the role that imbalances in these ions play in a number of disease-related physiological processes.

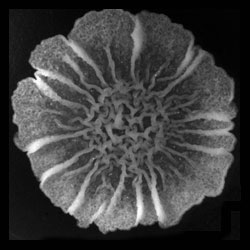

One recent focus of his studies has been how zinc regulates oocyte (egg cell) maturation and fertilization. Ultimately, his work could help us better understand infertility, cancer and certain bacterial infections.