William E. Moerner was at a conference in Brazil when he learned he’d be getting a Nobel Prize in chemistry. “I was incredibly excited and thrilled,” he said of his initial reaction.

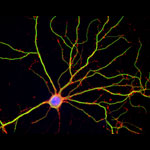

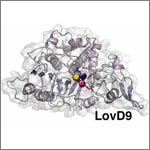

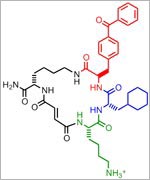

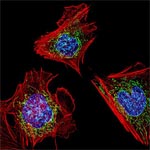

An NIGMS grantee at Stanford University, Moerner received the honor for his role in achieving what was once thought impossible—developing super-resolution fluorescence microscopy, which is so powerful it allows researchers to see and track individual molecules in living organisms in real time.

Nobel recipients usually learn of the prize via a phone call from Stockholm, Sweden, in early October. For those in the United States, the call typically comes between 2:30 a.m. and 5:45 a.m.

Every year, the NIGMS communications office prepares for the Nobel Prize announcements in physiology or medicine and chemistry, the categories in which our grantees are most likely to be recognized. If the Institute played a significant role in funding the prize-winning research, we work quickly to provide information and context to reporters covering the story on tight deadlines. We issue a statement, identify an in-house expert on the research and arrange interviews with reporters. It’s all to help get the word out about the research and the taxpayers’ role in supporting it.

This year’s in-house expert, Cathy Lewis, shared her thoughts on the prize to Moerner in an NIGMS Feedback Loop post. You can also read this year’s statement and see a full list of NIGMS-supported Nobel laureates.