Galina Lepesheva

Field: Biochemistry

Works at: Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN

Born, raised and studied in: Belarus

To unwind, she: Reads, travels, spends time with her family

Galina Lepesheva knows that kissing bugs are anything but romantic. When the lights get low, these blood-sucking insects begin feasting—and defecating—on the faces of their sleeping victims. Their feces are often infected with a protozoan (a single-celled, eukaryotic parasite) called Trypanosoma cruzi that causes Chagas disease. Lepesheva has developed a compound that might be an effective treatment for Chagas. She has also tested the substance, called VNI, as a treatment for two related diseases—African sleeping sickness and leishmaniasis.

“This particular research is mainly driven by one notion: Why should people suffer from these terrible illnesses if there could be a relatively easy solution?” she says.

Lepesheva’s Findings

Currently, most cases of Chagas disease occur in rural parts of Mexico, Central America and South America. According to some estimates, up to 1 million people in the U.S. could have Chagas disease, and most of them don’t realize it. If left untreated, the infection is lifelong and can be deadly.

The initial, acute stage of the disease is usually mild and lasts 4 to 8 weeks. Then the disease goes dormant for a decade or two. In about one in three people, Chagas re-emerges in its life-threatening, chronic stage, which can affect the heart, digestive system or both. Once chronic Chagas disease develops, about 60 percent of people die from it within 2 years.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has targeted Chagas disease as one of five “neglected parasitic infections,” indicating that it warrants special public health action.

“Chagas disease does not attract much attention from pharmaceutical companies,” Lepesheva says. Right now, there are only two medicines to treat it. They are only available by special request from the CDC, aren’t always effective and can cause severe side effects.

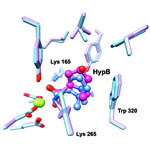

Lepesheva’s research focuses on a particular enzyme, CYP51, that is the target of some anti-fungal medicines. If CYP51 can also act as an effective drug target for the parasites that cause Chagas, her work might help meet an important public health need.

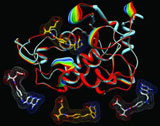

CYP51 is found in all kingdoms of life. It helps produce molecules called sterols, which are essential for the development and viability of eukaryotic cells. Lepesheva and her colleagues are studying VNI and related compounds to examine whether they can block the activity of CYP51 in human pathogens such as protozoa, but do no harm to the enzyme in mammals. In other words, her goal is to cripple disease-causing organisms without creating side effects in infected humans or other mammals.

Lepesheva has tested the effectiveness of VNI on Chagas-infected mice. Remarkably, it has worked 100 percent of the time, curing both the acute and chronic stages of the disease. It acts by preventing the protozoan from establishing itself in the host’s body. If it is similarly effective in humans, VNI could become the first reliable treatment for Chagas disease.