Cell biologists would love to shrink themselves down and actually see, touch and hear the inner workings of cells. Because that’s impossible, they have developed an ever-growing collection of microscopes to study cellular innards from the outside. Using these powerful tools, researchers can exhaustively inventory the molecular bits and pieces that make up cells, eavesdrop on cellular communication and spy on cells as they adapt to changing environments.

In recent years, scientists have developed new cellular imaging techniques that allow them to visualize samples in ways and at levels of detail never before possible. Many of these techniques build upon the power of electron microscopy (EM) to see ever smaller details.

Unlike traditional light microscopy, EM uses electrons, not light, to create an image. To do so, EM accelerates electrons in a vacuum, shoots them out of an electron gun and focuses them with doughnut-shaped magnets onto a sample. When electrons bombard the sample, some pass though without being absorbed while others are scattered. The transmitted electrons land on a detector and produce an image, just as light strikes a detector (or film) in a camera to create a photograph.

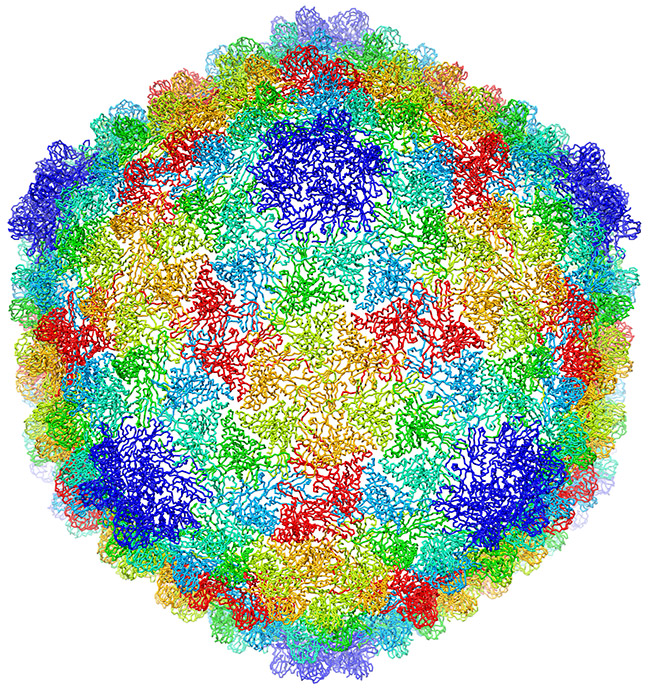

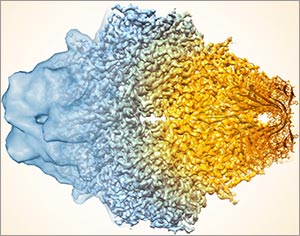

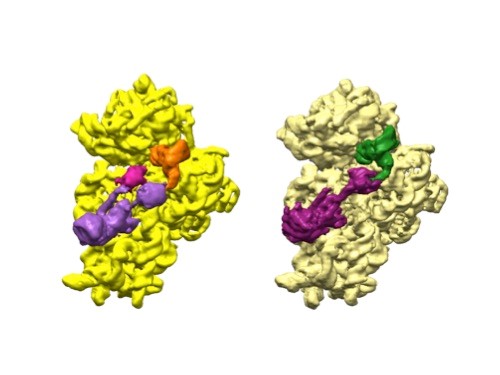

This image, showing a single protein molecule, is a montage. It was created to demonstrate how dramatically cryo-EM has improved in recent years. In the past, cryo-EM was only able to obtain a blobby approximation of a molecule’s shape, like that shown on the far left. Now, the technique yields exquisitely detailed images in which individual atoms are nearly visible (far right). Color is artificially applied. Credit: Veronica Falconieri, Subramaniam Lab, National Cancer Institute.

Transmission electron microscopes can magnify objects more than 10 million times, enabling scientists to see the outline and some details of cells, viruses and even some large molecules. A relatively new form of transmission electron microscopy called cryo-EM enables scientists to view specimens in their natural or near-natural state without the need for dyes or stains.

In cryo-EM—the prefix cry- means “cold” or “freezing”—scientists freeze a biological sample so rapidly that water molecules do not have time to form ice crystals, which could shove cellular materials out of their normal place. Cold samples are more stable and can be imaged many times over, allowing researchers to iteratively refine the image, remove artifacts and produce even sharper images than ever before. Continue reading “Cool Tools: Pushing the Limits of High-Resolution Microscopy”

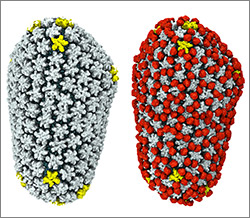

3D reconstructions of two stages in the assembly of the bacterial ribosome created from time-resolved cryo-EM images. Credit: Joachim Frank, Columbia University.

3D reconstructions of two stages in the assembly of the bacterial ribosome created from time-resolved cryo-EM images. Credit: Joachim Frank, Columbia University.

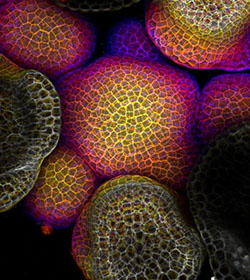

Credit: Arun Sampathkumar and Elliot Meyerowitz, California Institute of Technology.

Credit: Arun Sampathkumar and Elliot Meyerowitz, California Institute of Technology.

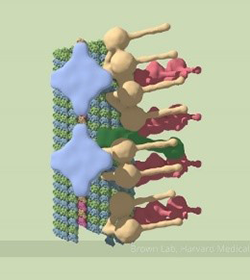

A partial model of a doublet microtubule. Credit: Veronica Falconieri.

A partial model of a doublet microtubule. Credit: Veronica Falconieri.