This is the third post in a new series highlighting NIGMS’ efforts toward developing a robust, diverse and well-trained scientific workforce.

Credit: Christa Reynolds.

Priscilla Del Valle

Academic Institution: The University of Texas at El Paso

Major: Microbiology

Minors: Sociology and Biomedical Engineering

Mentor: Charles Spencer

Favorite Book: The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks, by Rebecca Skloot

Favorite Food: Tacos

Favorite music: Pop

Hobbies: Reading and drinking coffee

It’s not every day that you’ll hear someone say, “I learned more about parasites, and I thought, ‘This is so cool!’” But it’s also not every day that you’ll meet an undergraduate researcher like 21-year-old Priscilla Del Valle.

BUILD and the Diversity Program Consortium

The Diversity Program Consortium (DPC) aims to enhance diversity in the biomedical research workforce through improved recruitment, training and mentoring nationwide. It comprises three integrated programs—Building Infrastructure Leading to Diversity (BUILD), which implements activities at student, faculty and institutional levels; the National Research Mentoring Network (NRMN), which provides mentoring and career development opportunities for scientists at all levels; and the Coordination and Evaluation Center (CEC), which is responsible for evaluating and coordinating DPC activities.

Ten undergraduate institutions across the United States have received BUILD grants, and together, they serve a diverse population. Each BUILD site has developed a unique program intended to engage and prepare students for success in the biomedical sciences and maximize opportunities for research training and faculty development. BUILD programs include everything from curricular redesign, lab renovations, faculty training and research grants, to student career development, mentoring and research-intensive summer programs.

Del Valle’s interest in studying infectious diseases and parasites is motivating her to pursue an M.D./Ph.D. focusing on immunology and pathogenic microorganisms. Currently, Del Valle is a junior at The University of Texas at El Paso (UTEP)’s BUILDing SCHOLARS Center. BUILDing SCHOLARS, which stands for “Building Infrastructure Leading to Diversity Southwest Consortium of Health-Oriented Education Leaders and Research Scholars,” focuses on providing undergraduate students interested in the biomedical sciences with academic, financial and professional development opportunities. Del Valle is one of the first cohort of students selected to take part in this training opportunity.

BUILD scholars receive individual support through this training model, and Del Valle says she likes “the way that they [BUILDing SCHOLARS] take care of us and the workshops and opportunities that we have.”

Born in El Paso, Texas, Del Valle moved to Saltillo, Mexico, where she spent most of her childhood. Shortly after graduating from high school, she returned to El Paso to start undergraduate courses at El Paso Community College (EPCC), to pursue an M.D. Del Valle explains that in Mexico, unlike in the United States, careers in medical research are not really emphasized in the student community or in society, so she did not have firsthand experience with research.

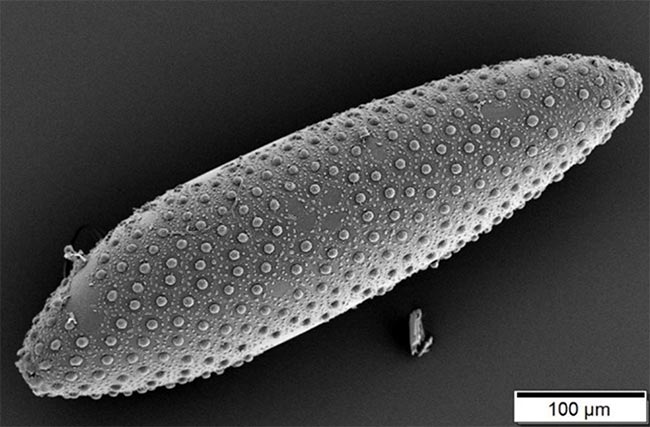

Del Valle discovered her passion for research when she was assigned a project on malaria as part of an EPCC course. She was fascinated by the parasite that causes malaria. “It impressed me how something so little could infect a person so harshly,” she says. Continue reading “Bit by the Research Bug: Priscilla’s Growth as a Scientist”