Elizabeth Grice

First job: Detasseling corn

Favorite food: Chocolate

Pets: An adopted shelter cat, Dolce

Favorite city: Athens, Greece

Hidden talent: Baking creative desserts

Credit: Bill Branson, NIH

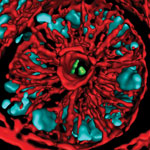

Imagine a landscape with peaks and valleys, folds and niches, cool, dry zones and hot, wet ones. Every inch is swarming with diverse communities, but there are no cities, no buildings, no fields and no forests.

You’ve probably thought little about the inhabitants, but you see their environment every day. It’s your largest organ—your skin.

Elizabeth Grice, an assistant professor at the University of Pennsylvania, studies the skin microbiome to learn how and why bacteria colonize particular places on the body. Already, she’s found that the bacterial communities on healthy skin are different from those on diseased skin.

She hopes her work will point to ways of treating certain skin diseases, especially chronic wounds. “I like to think that I am making discoveries that will impact the way medicine is practiced,” she says.

Grice’s Findings

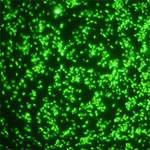

To investigate what role bacteria play in diabetic wounds, Grice and her colleagues took skin swabs from both diabetic and healthy mice, and then compared the two. They found that diabetic mice had about 40 times more bacteria on their skin, but it was concentrated into few species. A more diverse array of bacteria colonized the skin of healthy mice.

The researchers then gave each mouse a small wound and spent 28 days swabbing the sites to collect bacteria and observing how the skin healed. They found that wounds on diabetic mice started to increase in size at the same time as wounds on healthy mice began to heal. In about 2 weeks, most healthy mice looked as good as new. But most of the wounds on diabetic mice had barely healed even after a month.

Interestingly, bacterial communities in the wounds became more diverse in both groups of mice as they healed—although the wounds on diabetic mice still had less diversity than the ones on healthy mice.

“Bacterial diversity is probably a good thing, especially in wounds,” says Grice. “Often, potentially infectious bacteria are found on normal skin and are kept in check by the diversity of bacteria surrounding them.”

Grice and her colleagues also found distinctly different patterns of gene activity between the two groups of mice. As a result, the diabetic mice put out a longer-lasting immune response, including inflamed skin. Scientists believe prolonged inflammation might slow the healing process.

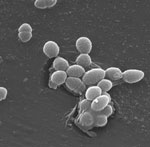

Grice’s team suspects that one of the main types of bacteria found on diabetic wounds, Staphylococcus, makes one of the inflammation-causing genes more active.

Now that they know more about the bacteria that thrive on diabetic wounds, Grice and her colleagues are a step closer to looking at whether they could reorganize these colonies to help the wounds heal.

Content adapted from the NIGMS Findings magazine article Body Bacteria.