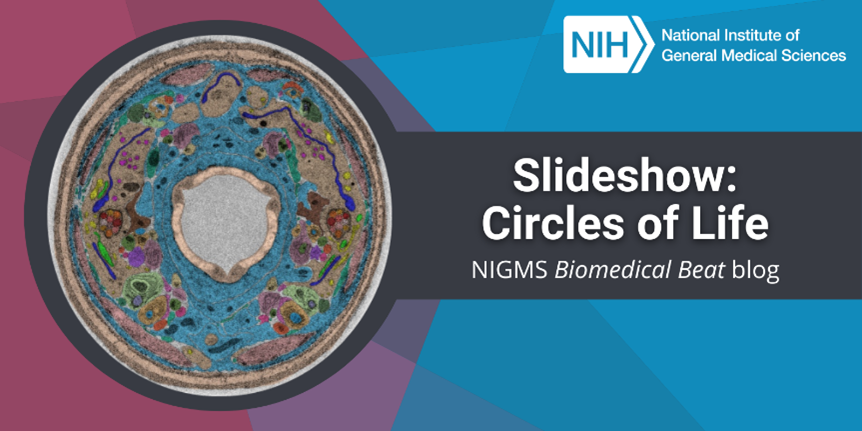

Every year on March 14, many people eat pie in honor of Pi Day. Mathematically speaking, pi (π) is the ratio of a circle’s circumference (the distance around the outside) to its diameter (the length from one side of the circle to the other, straight through the center). That means if you divide the circumference of any circle by its diameter, the solution will always be pi, which is roughly 3.14—hence March 14, or 3/14. But pi is an irrational number, which means that the numbers after the decimal point never end. With the help of computers, mathematicians have determined trillions of digits of pi.

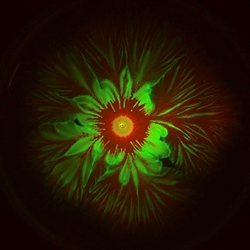

To celebrate Pi Day, check out this slideshow of circular microbes, research organisms, and laboratory tools (while you enjoy your pie, of course!). To explore more scientific photos, videos, and illustrations, visit our image and video gallery.

Continue reading “Slideshow: Circles of Life”

Credit: Liyang Xiong and Lev Tsimring, BioCircuits Institute, UCSD.

Credit: Liyang Xiong and Lev Tsimring, BioCircuits Institute, UCSD.

A cone snail shell. Credit: Kerry Matz, University of Utah.

A cone snail shell. Credit: Kerry Matz, University of Utah.

Microbiota in the intestines. Credit: iStock.

Microbiota in the intestines. Credit: iStock.