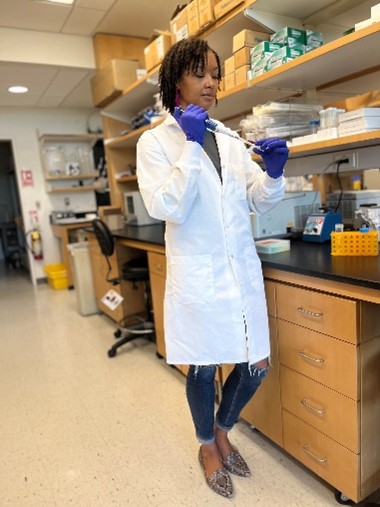

“It’s a thrill to make a discovery in science. In that moment, you’re the only one who knows about this new finding. Then you get to share that discovery with the world,” says Chelsey Spriggs, Ph.D. Dr. Spriggs is an assistant professor of cell and developmental biology at the University of Michigan (UMich) in Ann Arbor. We spoke with Dr. Spriggs about her early introduction to science through school science fairs, current research on viruses, and efforts to broaden participation in microbiology research across the world.

Get to Know Dr. Spriggs

- Books or movies? Books

- Coffee or tea? Coffee

- Favorite music genre? R&B (’90s and ’00s)

- Cats or dogs? Guinea pigs

- Early bird or night owl? Early bird

- Childhood dream job? Veterinarian

- Favorite hobby? Painting

- Favorite pipette size? 200uL

- Favorite lab tool? Confocal microscope

Q: How did you first become interested in science?

A: I’ve always been curious about science. I had wonderful science teachers growing up, but competing in science fairs was also a big part of it. My mom, who isn’t a scientist at all, helped me brainstorm great ideas to test and always made the process fun for me. The coolest science fair project I did was in 8th grade, and it was called A Shocking Development. I tested how a tiny electrical current applied to small radish-like plants through buried wires affected the plants’ growth. The electricity made the plants grow faster and taller! I won the science fair that year. The next year, I expanded the experiment and learned that too much electricity could be bad for the plants—if they were exposed for too long, they grew too fast, and their skinny stems couldn’t support the size of the plant, so they fell over.

My teachers noticed that I was having fun doing science fair experiments and recommended that I sign up for a summer research program. I spent a few weeks away at a college to learn about science and basic research techniques, like how to use a pipette.

Q: What was your path to becoming a researcher?

A: After graduating from high school, I went to Michigan State University (MSU) in East Lansing for undergrad. I originally thought that I would major in biology, but learning about viruses and bacteria sounded interesting, so I chose to study microbiology instead. I worked in a lab for 2 years and saw how much fun research could be. But at that point, I’d already decided that I wanted to go to medical school, and I stuck with that plan.

I spent about 3 months in medical school before I realized that my true calling was in research. I left and worked for a year in my undergrad advisor’s lab back at MSU before applying to Ph.D. programs. She was a tremendous help. I didn’t know the process for grad school applications, and she helped me every step of the way.

In the end, I studied for my Ph.D. at Northwestern University in Chicago, in the lab of Laimonis Laimins, Ph.D. He investigates how human papillomaviruses, which can cause cancer, control host cells for their own survival. My experience in the Laimins lab solidified my desire to start my own lab studying viruses, so I pursued a postdoctoral (postdoc) research job at UMich with Billy Tsai, Ph.D., studying polyomaviruses. There are many polyomaviruses, including some that can cause cancer. For example, Merkel cell polyomavirus (MCPyV) causes Merkel cell carcinoma, a type of skin cancer. I studied a polyomavirus called SV40 to learn more about how it and the other members of the polyomavirus family, especially MCPyV, infect cells.

SV40, like MCPyV, must enter the cell nucleus to cause infection because it needs the cell’s DNA replication machinery to make new virus particles. However, at the time, researchers didn’t know how the virus gets into the nucleus. Through my postdoc research, I learned that host cell protein complexes in the nuclear envelope grab SV40 and shuttle it into the nucleus.

Q: What does your lab study?

A: My lab is using MCPyV to investigate how host cell organelles or proteins are involved in moving polyomaviruses through the cytoplasm and into the nucleus. One question we’re trying to answer is if host cell motor proteins, which “walk” along the cytoskeleton to move cargo like organelles or vesicles, transport polyomaviruses to the nucleus.

Understanding the basic biology of how the virus and host interact is incredibly important for figuring out how to prevent viral infections and their long-term impacts, like cancer. Our work could identify differences in how polyomaviruses with cancer-causing potential and those without interact with their host cells. It may also lead to discovering a specific step in the infection process that medicines could disrupt to prevent infection.

Q: What do you consider your biggest accomplishment so far in your career?

A: Having my own research lab, which has been a dream of mine ever since I met my undergrad advisor at MSU, is my biggest accomplishment. I’m also proud of the environment I’ve built. I wanted to create a lab where we not only do really cool science, but where everyone is welcomed and supported. I wanted my students to be able to focus on their science because they felt safe to be themselves.

Q: What are you involved with outside the lab?

A: I cofounded the Black Microbiologists Association

(BMA) in 2020 and am its treasurer and director of finance and budgeting. We created BMA in response to the underrepresentation of Black scientists in microbiological education, training, and research. Currently, we have about 600 members from around the world.

Some of the activities we coordinate include a journal club where we pair a Ph.D. scientist with an undergraduate or graduate student to review a recently published article and write a short summary of it, which is then published in the journal Nature Microbiology in a series titled Amplifying diverse voices. We’re launching a monthly series of virtual trainings on topics like how to find a mentor, identify a good lab environment, and apply for grants.

Q: What advice would you give to students who are interested in pursuing a career in science?

A: Don’t limit yourself to only what you think you’re capable of. If you’re from a traditionally underrepresented background and don’t see yourself represented in your field of choice, it can be particularly hard to imagine yourself in that role. But remind yourself that you do belong in science, and don’t let doubt stop you from chasing your goals.

Dr. Spriggs’ research is supported by the NIGMS Maximizing Opportunities for Scientific and Academic Independent Careers program through grant R00GM141365.

Other Posts You May Like

- Understanding Signaling Through Cell Membranes: Q&A With Chrystal Starbird

- Bil Clemons: Following Scientific Curiosity

- From Science Fair to Science Lab: Q&A With Chelsey Spriggs

- Haley Bridgewater: Taking the Sting Out of Vaccines

- Investigating the Inner Workings of Ion Channels With Sudha Chakrapani