Credit: Jennifer Doudna

Jennifer Doudna

Fields: Biochemistry and structural biology

Studies: New genome editing tool called CRISPR

Works at: University of California, Berkeley

Raised in: Hilo, Hawaii

Studied at: Pomona College, Harvard University

Recent honors: Winner of the

Lurie Prize in the Biomedical Sciences

, an annual award that recognizes outstanding achievement by promising scientists age 52 or younger

If she couldn’t be a scientist, she’d like to be: A papaya farmer or an architect

Jennifer Doudna likes to get her hands dirty. Literally. When she’s not in her laboratory, she can often be found amid glossy green leaves and brightly colored fruit in her Berkeley garden. She recently harvested her first three strawberry guavas.

Coaxing tropical fruit plants from her childhood home in Hawaii to grow in Northern California is more than just a hobby—it’s an intellectual challenge.

“I like solving puzzles, I like the process of figuring things out, and I enjoy working with my hands,” says Doudna. “Those things were what really drew me to science in the beginning.”

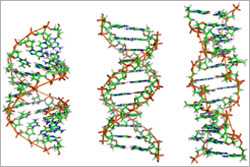

Since she was a graduate student, Doudna’s professional puzzle has been RNA, a type of genetic material inside our cells. Recently, there has been an explosion of discoveries about the many roles RNA molecules play in the body. Doudna’s work probes into how RNA molecules work, what 3-D shapes they form and how their structures drive their functions.

“I’ve been fascinated by understanding RNA at a mechanistic level,” Doudna says.

While teasing out answers to these fundamental questions, Doudna’s lab has played a leading role in a discovery that is upending the field of genetic engineering, with exciting implications for human health.

Her Findings

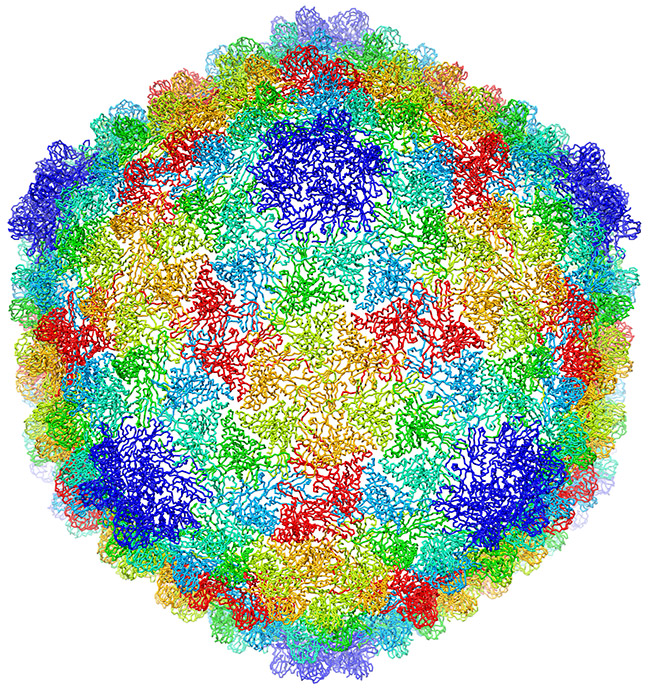

The discovery started with bacteriophages—viruses that infect bacteria, just like the common cold infects humans. About 10 years ago, researchers using high-powered computing to sift through bacterial genomes began to find mysterious repetitive gene sequences that matched those from viruses known to infect the bacteria. The researchers named these sequences “clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats,” or CRISPRs for short.

Over the next few years, scientists came to understand that these CRISPR sequences are part of something not previously thought to exist—an adaptive bacterial immune system, which remembers viruses fought off before and raises a response to fight them when exposed again. CRISPRs were this immune system’s reference library, holding records of viral exposure.

Somehow, bacteria with a CRISPR-based immune system (there are three types now known to scientists) use these records to command certain proteins to recognize and chop up DNA from returning viruses.

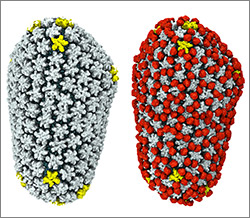

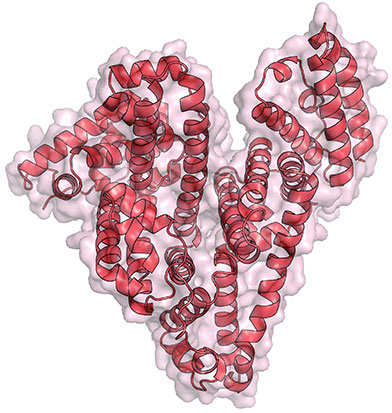

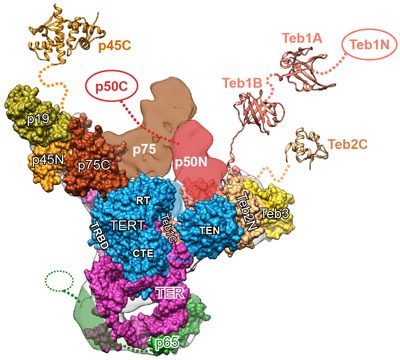

Wanting to know more about this process, Doudna’s team picked one protein in a CRISPR-based defense system to study. This protein, called Cas9, had been identified by other researchers as being essential for protection against viral invasion.

To their delight, Doudna’s group had hit the jackpot. Cas9 turned out to be the system’s scalpel. Once CRISPR identifies a DNA sequence from the invading virus, Cas9 slices the sequence out of the viral genome, destroying the virus’s ability to copy itself.

Doudna’s lab and their European collaborators also identified the other key components of the CRISPR-Cas9 system—two RNA molecules that guide Cas9 to the piece of viral DNA identified by CRISPR.

Even more importantly, the researchers showed that the two guide RNAs could be manipulated in the lab to create a tool that both recognizes any specified DNA sequence and carries Cas9 there to make its cut.

“That was really where we made the connection between the basic, curiosity-driven research that we were doing and recognizing that we had in our hands something that could be a very powerful technology for genome editing,” remembers Doudna.

She was right. After publication of their 2012 paper, the field of CRISPR-guided genetic manipulation exploded. Labs around the world now use the tool Doudna’s team developed to cut target gene sequences in organisms ranging from plants to humans. The technique is already replacing more time-consuming, less-reliable methods of creating ‘knock-out’ model organisms (those missing a specific gene) for laboratory research. CRISPR-based editing even allows more than one gene to be knocked out at the same time, something that was not possible with previous genome-editing techniques.

The ability of CRISPR systems to recognize DNA sequences with extraordinary precision also holds potential for human therapeutics. For example, a paper from another laboratory published early this year showed that, in a mouse model, CRISPR-based editing could cut out and replace a defective gene responsible for a type of muscular dystrophy. Researchers are testing similar CRISPR-based techniques in models of human diseases ranging from cystic fibrosis to blood disorders.

Doudna is a co-founder of two biotechnology companies hoping to harness the potential of CRISPR-based genome editing. Although the technology holds great promise, she acknowledges that much work needs to be done before CRISPR can be considered safe for human trials. Major challenges include assuring that no off-target cuts are made in the genome and finding a safe way to deliver the editing system to living tissues.

She is also excited to continue working with her research team, advancing the basic understanding of the CRISPR-based system.

“I’m very interested in seeing what we can contribute to the whole question about how you deliver a technology like this, how you can use it therapeutically in an organism. That’s an area where we hope that our biochemical understanding of this system will be able to contribute,” she concludes.