In less than two decades, RNA interference (RNAi)—a natural process cells use to inactivate, or silence, specific genes—has progressed from a fundamental finding to a powerful research tool and a potential therapeutic approach. To check in on this fast-moving field, I spoke to geneticists Craig Mello of the University of Massachusetts Medical School and Michael Bender of NIGMS. Mello shared the 2006 Nobel Prize in physiology or medicine with Andrew Fire ![]() of Stanford University School of Medicine for the discovery of RNAi. Bender manages NIGMS grants in areas that include RNAi research.

of Stanford University School of Medicine for the discovery of RNAi. Bender manages NIGMS grants in areas that include RNAi research.

How have researchers built on the initial discovery of RNAi?

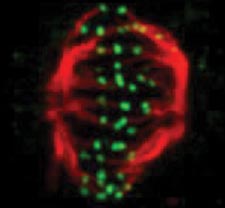

A scientific floodgate opened after the 1998 discovery that it was possible to switch off specific genes by feeding microscopic worms called C. elegans double-stranded RNA that had the same sequence of genetic building blocks as a target gene. (Double-stranded RNA is a type of RNA molecule often found in, or produced by, viruses.) Scientists investigating gene function quickly began to test RNAi as a gene-silencing technique in other organisms and found that they could use it to manipulate gene activity in many different model systems. Additional studies led the way toward getting the technique to work in cells from mammals, which scientists first demonstrated in 2001. Soon, researchers were exploring the potential of RNAi to treat human disease.

Continue reading “Field Focus: Progress in RNA Interference Research”