When someone mentions aging, you may think of visible changes, like graying hair. Scientists can see signs of aging in cells, too. Understanding how basic cell processes are involved in aging is a first step to help people lead longer, healthier lives. NIGMS-funded researchers are discovering how aging cells change and applying this knowledge to health care.

Discovering the Wisdom of Worms

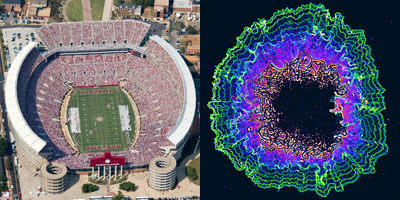

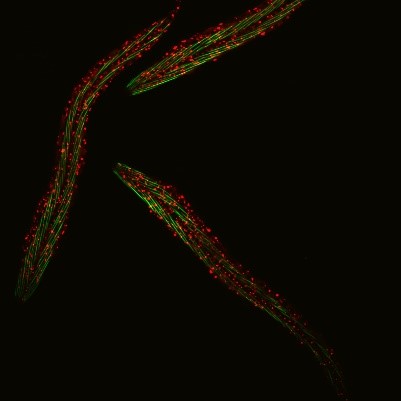

C. elegans with a ribosomal protein glowing red and muscle fibers glowing green. Credit: Hannah Somers, Mount Desert Island Biological Laboratory.

C. elegans with a ribosomal protein glowing red and muscle fibers glowing green. Credit: Hannah Somers, Mount Desert Island Biological Laboratory.

Aric Rogers, Ph.D., and Jarod Rollins, Ph.D., assistant professors of regenerative biology and medicine at Mount Desert Island (MDI) Biological Laboratory in Bar Harbor, Maine, are investigating aging by studying a tiny roundworm, Caenorhabditis elegans. Researchers often study C. elegans because, though it may seem drastically different from humans, it shares many genes and molecular pathways with us. Plus, its 2- to 3-week lifespan enables researchers to quickly see the effects of genetic or environmental factors on aging.

Drs. Rogers and Rollins investigate how C. elegans expresses genes differently under dietary restriction, enabling it to live longer. Understanding how genes are expressed when organisms live an extended life sheds light on the genetics underlying aging. This information could help researchers develop drugs or behavior modification programs that prolong life and delay the onset of age-related diseases such as heart disease, diabetes, cancer, and dementia.

Continue reading “Teaching Old Cells New Tricks: Insights Into Molecular-Level Aging”

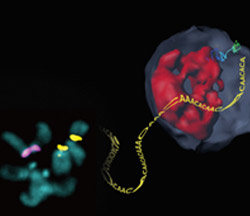

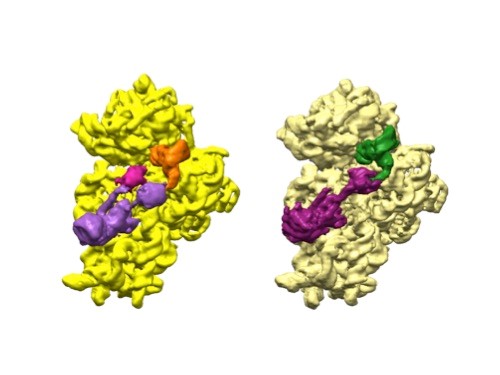

3D reconstructions of two stages in the assembly of the bacterial ribosome created from time-resolved cryo-EM images. Credit: Joachim Frank, Columbia University.

3D reconstructions of two stages in the assembly of the bacterial ribosome created from time-resolved cryo-EM images. Credit: Joachim Frank, Columbia University.