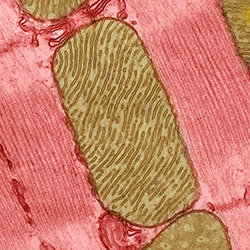

Scientists have identified a new family of proteins that, like the targets of penicillin, help bacteria build their cell walls. The finding might reveal a new strategy for treating a range of bacterial diseases.

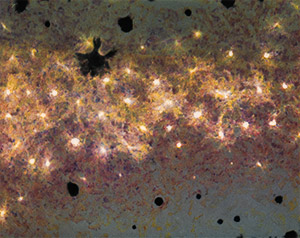

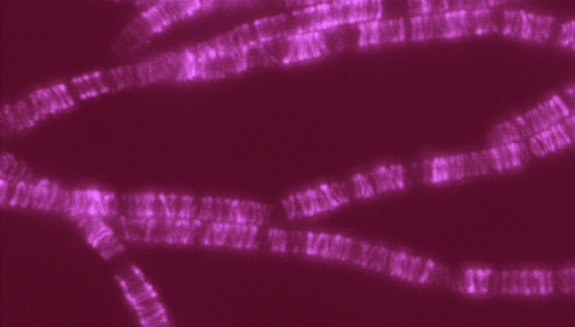

The protein family is nicknamed SEDS, because its members help control the shape, elongation, division and spore formation of bacterial cells. Now researchers have proof that SEDS proteins also play a role in constructing cell walls. This image shows the movement of a molecular machine that contains a SEDS protein as it constructs hoops of bacterial cell wall material.

Any molecule involved in building or maintaining cell walls is of immediate interest as a possible target for antibiotic drugs. That’s because animals, including humans, don’t have cell walls—we have cell membranes instead. So disabling cell walls, which bacteria need to survive, is a good way to kill bacteria without harming patients.

This strategy has worked for the first antibiotic drug, penicillin (and its many derivatives), for some 75 years. Now, many strains of bacteria have evolved to resist penicillins—and other antibiotics—making the drugs less effective.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, drug-resistant strains of bacteria ![]() infect at least 2 million people, killing more than 20,000 of them in the U.S. every year. Identifying potential new drug targets, like SEDS proteins, is part of a multi-faceted approach to combating drug-resistant bacteria.

infect at least 2 million people, killing more than 20,000 of them in the U.S. every year. Identifying potential new drug targets, like SEDS proteins, is part of a multi-faceted approach to combating drug-resistant bacteria.