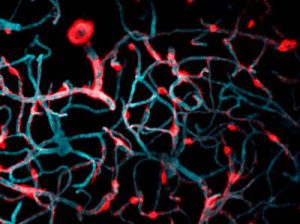

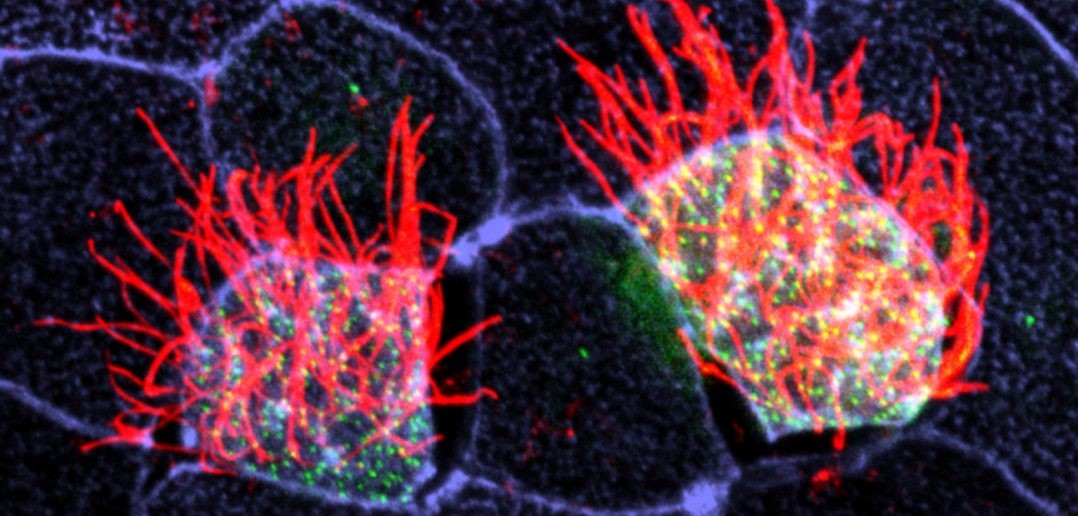

The red spray pictured here may look like fireworks erupting across the night sky on July 4th, but it’s actually a rare glimpse of tiny protein strands called microtubules sprouting and growing from one another in a lab. Microtubules are the largest of the molecules that form a cell’s skeleton. When a cell divides, microtubules help ensure that each daughter cell has a complete set of genetic information from the parent. They also help organize the cell’s interior and even act as miniature highways for certain proteins to travel along.

As their name suggests, microtubules are hollow tubes made of building blocks called tubulins. Scientists know that a protein called XMAP215 adds tubulin proteins to the ends of microtubules to make them grow, but until recently, the way that a new microtubule starts forming remained a mystery.

Sabine Petry and her colleagues at Princeton University developed a new imaging method for watching microtubules as they develop and found an important clue to the mystery. They adapted a technique called total internal reflection fluorescence (TIRF) microscopy, which lit up only a tiny sliver of a sample from frog egg (Xenopus) tissue. This allowed the scientists to focus clearly on a few of the thousands of microtubules in a normal cell. They could then see what happened when they added certain proteins to the sample.

Continue reading “Molecular Fireworks: How Microtubules Form Inside Cells”

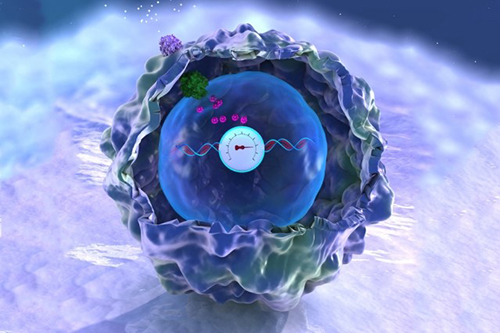

Cells covered with cilia (red strands) on the surface of frog embryos. Credit: The Mitchell Lab.

Cells covered with cilia (red strands) on the surface of frog embryos. Credit: The Mitchell Lab.