Jennifer Doudna, Ph.D. Credit: University of California, Berkeley.

Jennifer Doudna, Ph.D. Credit: University of California, Berkeley.

The 2020 Nobel Prize in Chemistry was awarded to Jennifer Doudna, Ph.D., and Emmanuelle Charpentier, Ph.D., for the development of the gene-editing tool CRISPR. Dr. Doudna shared her thoughts on the award and answered questions about CRISPR in a live chat with NIH Director Francis S. Collins, M.D., Ph.D. Here are a few highlights from the interview.

Q: How did you find out that you won the Nobel Prize?

A: It’s a little bit of an embarrassing story. I slept through a very important phone call and finally woke up when a reporter called me. I was just coming out of a deep sleep, and the reporter was asking, “What do you think about the Nobel?” And I said, “I don’t know anything about it. Who won it?” I thought they were asking for comments on somebody else who won it. And she said, “Oh my gosh! You don’t know! You won it!”

Q: Say a little bit about what this prize is for. What’s CRISPR?

A: CRISPR is a tool for genome editing. That means changing DNA in a precise way in cells that can allow very tiny changes, including changing a single letter in the genetic code, all the way to cutting out genes or entire pathways and replacing them. It’s a tool for manipulating DNA that actually evolved a long time ago, probably long before humans came along, as a bacterial immune system. It’s a way that bacteria fight viruses.

Q: Does CRISPR have therapeutic applications? Will it lead to gene therapies that could save lives?

A: I think it will, with a little caveat that I think increasingly it’s not about whether this can work; it’s about how do we make sure it’s affordable to people who need it. I’ll give you an example. With sickle cell disease, we’ve already seen incredible advances. We’ve seen an announcement in the last year of a patient, Victoria Gray, who has been effectively cured of her sickle cell disease using CRISPR. But for sickle cell right now, CRISPR has to be deployed using a bone marrow transplant. Cells are taken from a patient and edited and then replaced by bone marrow transplantation. Very expensive. Obviously not an easy procedure, even though it’s become more routine. Now what I think we need to do is increasingly focus on developing the technology in ways that will make it accessible and affordable to those who need it, not just here in the U.S., but also globally.

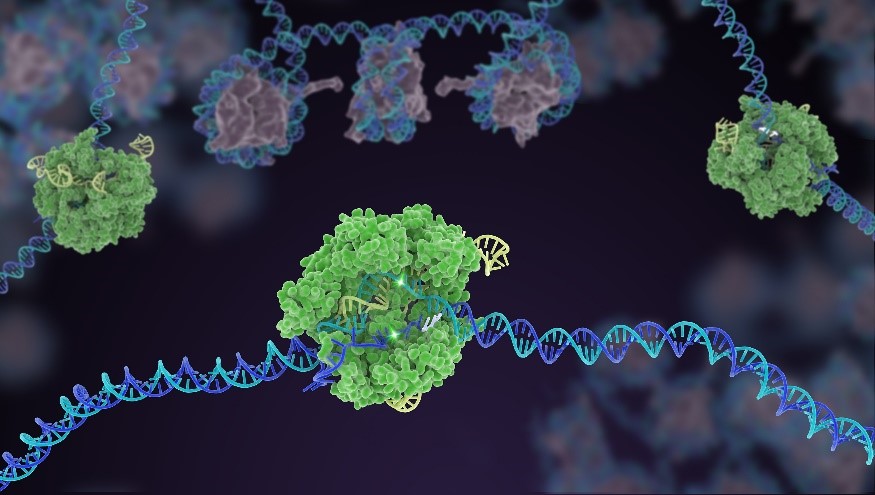

In CRISPR, a small strand of RNA identifies a specific chunk of DNA. Then the enzyme Cas9 (green) swoops in and cuts the double-stranded DNA (blue/purple) in two places, removing the specific chunk. Credit: Janet Iwasa for the Innovative Genomics Institute at UC Berkeley.

In CRISPR, a small strand of RNA identifies a specific chunk of DNA. Then the enzyme Cas9 (green) swoops in and cuts the double-stranded DNA (blue/purple) in two places, removing the specific chunk. Credit: Janet Iwasa for the Innovative Genomics Institute at UC Berkeley.

Q: Can you say a word about ethical issues in gene editing?

A: It was clear early on in the development of CRISPR that it worked broadly in many different cell types, including in embryos. It’s important to appreciate that that use of genome editing is quite distinct from what we’re talking about when we talk about correcting a disease like sickle cell disease, where we’re making changes in a certain type of cell in a patient, but those changes aren’t inheritable by future generations. Whereas changes in human embryos or sperm or eggs—these are changes that can be passed on to future generations.

Very quickly I realized that as a scientist involved in the very original work around CRISPR, it was essential to be explaining it to people who are not scientists. And then working to ensure that there was, at least among the international scientific community, some common set of guidelines or criteria for proceeding with that type of very special application of CRISPR. Honestly, I’ve been very pleased over the last 5 years. I think this is a good direction that we’re in right now, where there really is a feeling among the international scientific community that we need to use appropriate restraint and stewardship of this powerful tool.

Q: This is the first time a Nobel Prize has been awarded to two women. How do you feel about being a pioneer in this way?

A: May this be a sign that times are changing and that we will see many more of such awards and recognitions going to women, where appropriate for their work. I think it’s really, really important for women and girls who are thinking about a career in one of the STEM fields to feel like they are welcomed into the field and that their work will be appreciated. It needs to be the case that we are all working together in a community of scientists—and we are of different genders, cultural backgrounds, personal circumstances, et cetera. I’ve now been running an academic research lab for 26 years, and I’ve seen over that period of time that the more diverse my group is, the better our science is.

Q: Any advice for young people who want to pursue a career in science?

A: My advice is: Go for it! Don’t let anybody tell you that you can’t do it. In my own personal experience and with people I know in science who are highly successful, it’s because they trusted their inner voice about science.

NIGMS funded Dr. Doudna’s CRISPR research for many years, most recently through grant P01GM051487. Dr. Doudna currently receives NIH support from the Office of the Director and the National Human Genome Research Institute.