Over the past 2 years, you’ve probably heard a lot about the spread of SARS-CoV-2—the virus that causes COVID-19—and the emergence of variants. The discovery and tracking of these variants is possible thanks to genomic surveillance, a technique that involves sequencing and analyzing the genomes of SARS-CoV-2 virus particles from many COVID-19 patients. Genomic surveillance has not only shed light on how SARS-CoV-2 has evolved and spread, but it has also helped public health officials decide when to introduce measures to help protect people.

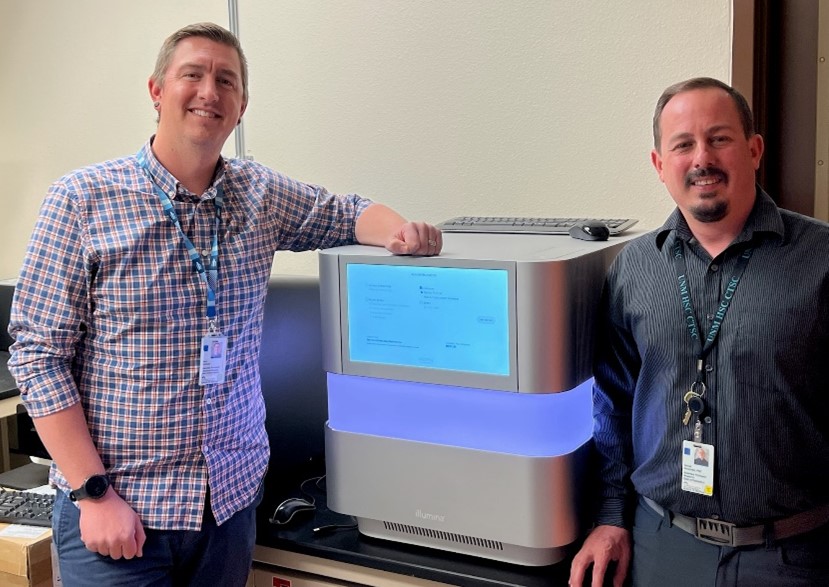

In December 2021, the NIGMS-supported SARS-CoV-2 genomic surveillance program at the University of New Mexico Health Science Center (UNM HSC) in Albuquerque detected the first known case of the Omicron variant in the state, which enabled a rapid public health response. The program’s co-leaders, assistant professors Darrell Dinwiddie, Ph.D., and Daryl Domman, Ph.D., were watching on high alert for it to enter New Mexico, and when it did, they were poised to quickly identify it:

- December 7: A patient tested positive for COVID-19 at the UNM hospital.

- December 9: The UNM HSC genomic surveillance program received a viral sample from the patient.

- December 10: Dr. Dinwiddie’s lab started sequencing the sample, a process that takes about 24 hours.

- December 12: Dr. Domman’s lab, which handles analysis of the SARS-CoV-2 genome sequences, determined that the sample was Omicron.

Drs. Dinwiddie and Domman immediately notified the New Mexico Department of Health, who released a public announcement the next day encouraging people to wear masks and receive COVID-19 vaccine booster shots to help reduce the variant’s spread. In all, it took less than a week from the time the patient was tested until a public announcement was made.

Prior to the pandemic, Dr. Dinwiddie used genomic sequencing to study other respiratory viruses, and Dr. Domman conducted genomic surveillance for cholera at a global level. As experts in the study of human pathogens, they were both able to rapidly shift their focus to the SARS-CoV-2 virus when the pandemic first began. They sequenced nearly every sample positive for SARS-CoV-2 from both the UNM hospital and across New Mexico from a large diagnostic testing company called TriCore Reference Laboratories. “UNM and its hospital, the New Mexico Department of Health, and TriCore Reference Laboratories have been a tightly integrated working group. It’s been a really nice collaborative effort where we function as one large team for the public good of New Mexico,” says Dr. Domman.

Drs. Dinwiddie and Domman plan to continue conducting SARS-CoV-2 genomic surveillance as well as extend their genomic surveillance efforts to other pathogens, including antibiotic-resistant bacteria. “The collaboration between the members of the SARS-CoV-2 genomic surveillance program expanded during the pandemic, and now we’re pushing into new areas. We believe that genomic surveillance of pathogens has many uses,” says Dr. Dinwiddie. For instance, the genomic surveillance program could warn of an uptick in certain antibiotic-resistant infections and issue a warning to encourage potentially lifesaving precautions, just like they did for the Omicron variant.

The UNM HSC SARS-CoV-2 genomic surveillance program is supported by NIGMS grant P20GM130422.